DAB Matula Thoughts Nov 4, 2016

3975 words

Preface. This monthly communication from the University of Michigan Department of Urology & David A. Bloom is usually sent by email or posted on line at matulathoughts.org on the first Friday of each month.

One.

Autumn has been spectacular at Michigan Urology academically and around Ann Arbor visually. Seasonal changes on the Huron River were up to high expectations as leaves colored out and birds headed south. You don’t have to travel far outside of town to see crop harvesting has wound down, while distracting political signs along the roads are highlighting our national political schizophrenia. [Above: Huron River near Wagner Road. Below: Waterloo Road east of Chelsea, Michigan]

Nestled in the Midwest, we were spared Hurricane Matthew that hit Haiti, Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas in October. The biggest regional surprise was the overtime World Series victory of the Chicago Cubs over the Cleveland Indians, both teams having contested well. Births and other happy events also perked up this season, but we suffered losses. Madeline Horton, secretary of Jack Lapides and mother of Suzanne Van Appledorn (wife of Carl Van Appledorn, Nesbit 1972) passed away last month a few weeks short of her 100th birthday. Madeline was our urology librarian, a job largely obviated by the internet. I fondly remember her gracious welcome when I joined the University of Michigan Section of Urology in the early years of Ed McGuire’s leadership.

Final rules for the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) went into effect last month, instituting the Quality Payment Program (QPP) that begins its first performance period 58 days from now, by my count. This will significantly change the basis of physician payment and the rules are entrenched so deeply in federal regulation as to be practically bullet-proof from the impending presidential election or other short-term political processes. By November, it is pretty clear that another calendar year is coming to an end and it’s time to start serious planning for next year. Of course as a department of urology specifically, and as a large academic health center more generally, our planning has been on going in earnest for considerably longer than the past few days. Emerging out of many years of restricted capital investment in facilities and regional relationships we are in an unprecedented growth mode to more optimally fulfill our mission. This has been the first year of our new organizational paradigm for the University of Michigan Health System in which Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs of the University, Marschall Runge, added the Medical School deanship to his portfolio. A Health System Board along with Health System President, David Spahlinger, will manage the growing enterprise of hospital groups, medical practice, ambulatory clinics, regional affiliations, and other entities that have evolved to carry out our mission. These are good structural changes and superb individuals for the challenges ahead.

Our mission derives from our foundation as a public medical school in 1850 and is similar to the mission of all other medical schools, although the University of Michigan has long described itself as one of the “leaders and best”, a phrase that history shows we can rightly claim, for the most part. The mission is framed around three components – education, patient care, and research – deployed in that order as our medical school grew, adding its own contained hospital in 1869 and soon thereafter some of the world’s definitive basic science departments and research laboratories.

Two.

Silos of expertise necessarily accrued as the medical school and health care center in Ann Arbor grew more complex with the result that the overall management became increasingly disconnected from the loci of expertise at its many workplaces. The gemba, a Japanese term related to the Lean Process Methodology of the Toyota Corporation, describes where work is performed – the workplace. As Toyota, and later Detroit automotive manufacturing came to understand, microeconomic gembas understand their products, customers, and processes better than higher-level managers or accountants. Process improvement, value creation, efficiency, customer satisfaction, and employee satisfaction are best arbitrated “where the work is done” (i.e. the gemba) rather than in distant offices by managerial accounting.

Oddly, just as forward-thinking western businesses are embracing lean process thinking, large health care systems and governmental organizations are more rigidly holding on to managerial accountancy with its concomitant archipelago of cost centers. Of course any organization needs to understand and mitigate its costs, but lean process experience has shown that efficiency and value are a natural result of letting the gemba work as an organic community, rather than forcing its functions by the levers of managerial accounting. [Below: going home from work, a Diego Rivera mural detail – Detroit Institute of Arts]

Anyway, back to the triple mission: the University of Michigan Health System exists to educate the next generation of physicians and scientists, to expand the knowledge and technology base of health care, and to do these things in a milieu of cutting edge clinical care. The central organizing principle at play, that is the essential deliverable (and moral center) is kind and excellent patient-centered care, as we describe it in our department.

The future in healthcare will depend on our ability to weave silos together and innovate, creating new ideas, devices, and methods. In a larger sense innovation is the ability to find better solutions for the needs of a changing environment.

Three.

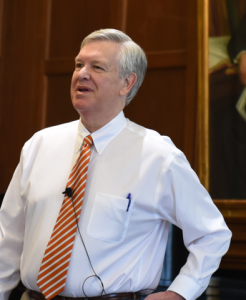

Leadership. A recurring aspiration of the University of Michigan is that it produces the “leaders and the best.” That phrase is functionally adjectival as with the leaders and the best engineers, teachers, athletes, lawyers, nurses, chemists, or physicians, for example. The leaders and best is less meaningful as a noun, for what does it really mean to be “the best” if not the best of some particular thing. The same holds true for leadership, in my opinion. The aspiration to be “a leader” as a generality carries a bit of a selfish sense with it, whereas the aspiration to lead one’s team to do its job well or otherwise fulfill its mission is more socially virtuous. The difference is perhaps one between the captain of a football team versus travelling CEO’s who jump among companies to exercise their managerial or accounting gifts. Without deep knowledge and investment in a particular organization, an itinerant leader is unlikely to inspire most organizations and its people to achieve their best social destiny. Another way to look at this is whether the leader’s primary goal is to be “the boss” by leading, managing, and controlling employees to achieve organizational targets, in contrast to a goal of helping the organization achieve an optimal state for its stakeholders.

What does a urology department need in a leader? I submit that first and foremost it needs someone who loves and practices urology robustly; former dean Allen Lichter once said – “for such a person patient care is a moral imperative, not something that is important enough unless it interferes with research.” Second, a clinical department needs an individual who understands the organizational mission and its history – these two things are inseparable, requiring more than just lip service to be truly known. Third, we require someone whom the faculty, residents, staff, and other stakeholders trust. Fourth, the department needs a person who can read the changing environment and find opportunities within it. Other attributes may be valued according to the specifics of each department, institution and moment in time, however “celebrity leadership” by itself should not be high on the list of qualities sought.

Four.

Until it fails, people don’t appreciate the beauty of a competent urinary system. Urologists are the essential attendants at that particular service station of life, but the necessity of professional detachment renders us susceptible to underestimating the angst and vulnerability of urologic patients. Finding the right balance between empathy and detachment is a personal matter, arbitrated by daily experience to the extent that we are influenced by our medical practices, role models (real and fictional), and general observations in life. To the extent that we pay attention to the real world around us and to the creative arts, we improve our practice of medicine.

Creative arts matter to medicine. The portrait of Dr. John Sassall by Berger & Mohr in A Fortunate Man, was an artful mix of empathy and detachment. The doctor had sufficient detachment to do what he needed medically for his patients, but retained unusual empathy for their social and economic comorbidities, even to his personal detriment.

In the visual arts for hundreds of years urinalysis, depicted by uroscopy flask (the matula), was the main symbol of medicine indicating the central importance of urine examination to understand disease. After 1816, when Laennec invented the stethoscope, the matula lost its place as the popular symbol of the medical profession. The stethoscope is certainly a less indelicate and a sturdier symbol than a glass urine flask. Imagine Gray’s Anatomy with the matula.

In literature Shakespeare was precocious in recognizing the fallacy of mistaking a clinical test for the actual patient when in this scene from Henry IV Falstaff asks a messenger what the physician thought of his uroscopy specimen:

“Sirrah, What says the doctor to my water?

He said, sir, the water itself was a good healthy water;

But for the party that owned it, he might have more diseases than he knew for.”

Visual art has only rarely portrayed urinary function. One example, the statue Manneken Pis (Little Man Pee, in Dutch. Above: Wikipedia illustration) designed by Hieronymus Duquesnoy the Elder around 1618-1619 has been stolen numerous times and the current version, dating from 1965, stands in Brussels. It is dressed in costumes according to a published schedule managed by “Friends of Manneken-Pis,” but I don’t know if University of Michigan colors have adorned it yet. Other versions of the statue exist regionally and in more distant sites in the world. Notice the arching back of the confident lad making his momentary mark on the world in front of him.

Depiction of urinary tract dysfunction in art is even less common than that of normal function. As common as dysuria and stranguria are for us humans, it’s rare to find them represented in the creative world. The Wayfarer, by Bosch, shows a man with the hunched-over posture typical of urinary distress, relegated to the central background of this curious painting. The painter, who died 500 years ago, lived in the historic low countries now called the Netherlands where he no doubt observed that characteristic posture often, as we do today in restrooms around the world.

[Hieronymus Bosch. Above: The Wayfarer. Below: voiding detail.]

The impact of nocturnal enuresis showed up in All’s Quiet on the Western Front, where a young soldier suffered with that burden.

My point is that creative arts sharpen our perception and groom our mirror neurons to make us better attendants at life’s service stations.

Five.

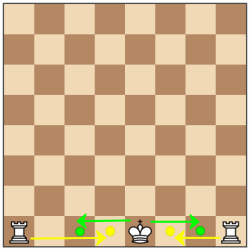

Castling. A few months ago this column referred to Richard Feynman’s metaphor related to mankind’s persistent search for central organizing principles, namely our curiosity to discover rules that govern the universe. He noted that, as we observe the “chess game of the world” and try to figure out how it works, every now and then “something like castling” occurs and blows our minds. That particular chess move is so far out of the box with respect to the other orderly rules and procedures of the game that it is, indeed, something of a miracle in that environment. (For chess aficionados the term rook may be preferable to castle, although castling sounds more appealing than rooking.)

It is human nature to seek rules. Prehistoric tribal priests, Ionian philosophers such as Aristotle, and recent scientists such as Feynman sought central organizing principles and rules. Unlike the explanations of the village priests, today’s principles of math, physics, chemistry, and biology are testable and verifiable or refutable. We have some ideas of why and how inorganic material things need to flow or seek equilibrium – principles of physics and chemistry govern their existence and fate. It is more of a mystery why biological things need to grow and humans, in particular, need to know things. No one has figured out, without invoking magical or religious paradigms, why our particulate niche in the universe is such as exception to what we perceive as the second law of thermodynamics. Perhaps our material, biological, and intellectual exception to the expanding and entropy-seeking universe is that strange miracle of “castling.” Bob Seger and The Silver Bullet Band expressed it more poetically in the 1980 song Against the Wind.

[Cosmic castling. Copper River. Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. Summer 2015]

Six.

It may seem an overstatement of human optimism to believe in the principle that the world you imagine is the world you are most likely to create, but a single person can have remarkable impact; Joan of Arc, Harriet Tubman, Abraham Lincoln, and Mahatma Gandhi are just a few examples. The impact of a single person, just as likely, can be darkly retrograde and numerous examples quickly come to mind.

Scientific thinking and modern technology have given mankind unprecedented tools to change the world with Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs as two of a myriad of other players. If you imagine a kind and just world, you will likely try to live by and spread those attributes. If you imagine a dog-eat-dog world and display that vision to those around you, that may likely become the reality you experience and leave behind. The possibility that a given leader can be good or bad for humanity might appear statistically random, that is stochastic, in terms of probability. On the other hand, if we carry the theme of castling to the idiosyncratic human experiment, it may not be so far-fetched to suggest that our genetic and epigenetic construction has built in a predilection to favor good over evil, making an individual more inclined to do the “right” rather than “wrong” thing at a given moment. That is, the elements leading up to a given personal decision are built upon individual upbringing, world-view, personal needs, perceived needs of our clan, and hope for the future. Adding all these elements, our prevailing human nature favors doing good, in the stoichiometric sense, most of the time.

Seven.

Where American health care will go next is unclear, no matter how the presidential election turns out next week. Problems abound in health care. The interface between patient and provider filling up with busy work and costs that distract from quality, safety, value, or satisfaction. Third party payers, regulators, public policy (even if well-intentioned) add an immense amount of “stuff” to be done before, during, and after the so-called patient encounter. While we prize innovation and the rewards of a free society, egregious exploitation of American healthcare consumers by industry seems to be getting worse and fuels demands for significant change. The EpiPen disgrace from the Pennsylvania company Mylan is only one of the many recent examples of human elements gone bad [JAMA 316:1439, 2016]. Why call out that one bad example among so many? My reason is simply that Mylan has made themselves such an easy target because they have been so sociopathically greedy.

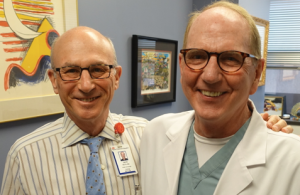

Our urology silo has been a good one locally and internationally, by and large. This is evident now in the midst of the residency selection process wherein we advocate for our particular training program in Ann Arbor, our specialty having attracted many of the best and brightest of this year’s senior medical students. My colleague and friend Mike Mitchell once called urology (pediatric urology, in particular) “a lovely specialty.” We practice at the cutting edge of technology, we improve patient lives, we fix things that are broken, we have the gift of long relationships with patients, and we generally get along well within our professional arena. As a medical student and resident myself, years ago, the attributes and role models of urology attracted me into the field – and these features of our profession continue to attract the superb students and residents to follow us.

Healthcare is changing and the urology of tomorrow will differ from what I experienced in my career. We have already transitioned from roles as independent urologists such as that of our predecessors Hugh Cabot, Reed Nesbit, and Jack Lapides. Our work to educate, treat patients, and expand the knowledge base of urology requires subspecialization and teams, large teams that transcend clinics, offices, department, and operating rooms. The complexity of science, technology, and healthcare delivery made this change inevitable, with marketplace pressures and regulatory actions accelerating change. The fee-for-service that largely defined health care over the past century is being rapidly displaced by alternate payment methodology, with a sharp focus on value and performance in play today. These were vague terms in health care until recently. Value and performance metrics in other endeavors have achieved growing visibility, so we shouldn’t be surprised to find them crossing over into health care. Michael Lewis’s Moneyball brought these terms to popular attention for baseball in 2014, with the movie in 2011, and healthcare was bound to follow. No doubt some sense of player value governed Theo Epstein in breaking the curses of the Red Sock and Chicago Cubs with their World Series droughts of 86 and 108 years, although it’s unlikely he discovered a novel set of useful metrics.

Eight.

Value & performance. A paper in JAMA last month demands attention. Vivian Lee et al from the University of Utah offered an original investigation with the lengthy title “Implementation of a value-driven outcomes program to identify high variability in clinical costs and outcomes and association with reduced cost and improved quality.” [JAMA 2016; 316(10): 1061-1072] A matching opinion piece in the same issue by Michael Porter and Thomas Lee offered glowing support: “From volume to value in health care”. [JAMA 2016; 316 (10): 1047-1048] While it is clear that value and performance measures will be tools to replace the American fee-for-service paradigm, the details in the Utah study are important, in particular the idea of an “opportunity index” that allows healthcare teams to understand their costs and develop lean processes that improve not just costs, but also quality, safety, and that once-vague attribute value. If leading health care centers believe in a world of value-based healthcare, such a world surely can be created. That world, however, will largely be built on the special skills of specialties and the complex teams of future medicine, wherein urologists with their singular skill sets that will likely always be prized.

Nine.

Stainless steel, eggs, & sperm. Innovation is a fundamental characteristic of biology, and randomness is always in play. At the cellular level we see innovation from the random errors of genetic transcription and the utilitarian retention of the changes in these DNA sequences when they provide a particular advantage, so one could argue that random chance lies behind all things that happen. Choice, however, somehow slips into play with life. Even low levels of cellular organization make choices and, by extension purposefully innovate in their lives. Nematodes (round worms) and flatworms, such as C. elegans and planaria, seek comfort and food as they move above their microcosms to discover opportunities or deterrents. Their actions are purposeful with deliberate directional choices as opposed to random Brownian motion. Each move is original in its own way, exploring new territory or retreating from threats. In the larger animal kingdom we see choice in behaviors of vertebrates, and hominids have taken choice and innovation to entirely new levels.

One hundred years ago Harry Brearley figured out a way to improve the quality and value of gun barrels. Gun performance deteriorated quickly after use because of barrel corrosion from moisture and gases after combustion, so Brearley considered variety of additives to create steel alloys with better resistance and found chromium most effective. This was already being used in the manufacture of steel for airplane engines, but one particular variant alloy had been difficult to examine microscopically because the etching processes used to prepare the samples for examination were far less effective than usual. The corrosion resistance problem for engine manufacturing proved to be a solution for gunsmiths.

Human innovation continues to advance even more remarkably. At our recent Nesbit meeting, Sherman Silber (Nesbit 1973) presented innovative work in reproductive medicine showing how pluripotent stem cells derived from skin cells can create eggs and sperm with full reproductive potential in normal mice.

Ten.

Silos. Silos are disparaged glibly in modern organizational discourse, but we owe them better appreciation. Some silos are storage vaults for coal, cement, or salt while others are biologic factories. Grain elevators, for example, store and ferment grain to produce silage for animal feed. Early farmers figured this out, probably noticing it by accident. After harvesting, clover, alfalfa, oats, rye, maize, or ordinary grasses are compressed in a closed space and after a brief aerobic phase, when trapped oxygen is consumed, anaerobic fermentation by desirable lactic acid bacteria begins to convert sugars to acids. Volatile fatty acids (acetic, lactic, butyric) are natural preservatives, lowering pH and creating a hostile environment for competing bacteria. Some microorganisms in the process produce vitamins such as folic acid or B12. Ever since the early days of farming indigenous microorganisms conducted successful fermentation, although modern farms utilize select strains of lactic acid bacteria or other microorganisms more efficiently. Because fermentation produces products that bacteria consume silage has less caloric content than the original forage, but the tradeoff is worthwhile due to the preservation and improved digestibility.

Thinking about silos, it seemed natural to take a trip to Chelsea, Michigan where the family-operated Chelsea Milling Company has been making baking mixes since 1930. Mabel White Holmes created the first prepared baking mix in the United States and her grandson, Howdy Holmes, presently runs this company of 300 employees producing 1.6 million boxes of products daily. Mabel White Holmes originally marketed her biscuit mix as “so easy even a man could do it” and Jiffy Mix with its memorable blue logo became one of America’s classic brands. Chelsea Milling makes and markets 19 mixes distributed to all 50 states and 32 countries. The Jiffy Mix corporate philosophy is employee-centric, much like Zingerman’s Community of Businesses and (we believe) the Department of Urology at the University of Michigan in the recognition of how silos build a community. The Jiffy Mix silos provide dry storage for wheat, while the people that work at the company provide the fermentation that makes and innovates superior products within a lean culture of thoughtful communication and collaborative decision-making. This is biologic castling.

[Next occupant?]

Whether for storage of salt or biofactories for silage, silos are ultimately useful only when working together as parts of farms and communities. This an analogy holds true in the political arena, where consensus is as important as victory. Our national and international communities suffer from self-righteous siloism. Current political rhetoric lacks dignity and respect to the point of ugliness, although the most corrosive disrespect is the a priori claim that the American political system is rigged, whether by one party, the media, or another nation. It is nonsense to be outraged that other countries are into our emails and elections – that’s exactly what we do as a nation and indeed it is the business of large nations to gather intelligence on competitors and get a thumb on the scales when possible. If our candidates say foolish things and our firewalls are weak then we should own the blame. With 4 days to our next national elections, this incivility of discourse is a short slippery slope to civil instability, which will not be good for anyone. The effect on healthcare will consequential and international scientific media as influential as The Lancet have taken the unprecedented step of hosting a US Election 2016 website: www.thelancet.com/USElection2016. Aside from parochial concerns such as healthcare, ultimately what will matter most for all of us on the planet after November 8 will be financial market and geopolitical stability – all other concerns pale in comparison.

[October driveway]

David A. Bloom

University of Michigan, Department of Urology, Ann Arbor