DAB What’s New February 3, 2017

February lows and highs; Sunday feelings, Monday facts

3916 words

One.

February is the nadir of winter as well as the shortest and most variable month, with average snowfalls of 13 inches, highs of 35℉, and lows of 20℉ in Ann Arbor (U.S. Climate Data. Wikipedia). Even though not quite the coldest month February seems the wintriest, lacking the enticements of December holidays and the exhilaration of January’s new year. This February, a regular one without the extra day, allows only 20 business days to pay the challenging bills of academic urology. Educational and research expenses always exceed their funding streams and require clinical and philanthropic dollars to maintain them.

[Michigan team and the Korle-Bu and Military Hospital staff, Accra.]

Last month 3 faculty and 2 residents escaped Michigan winter for a week of operating and teaching in Ghana. Sue and the late Carl Van Appledorn initiated this yearly trip and other generous donors help offset its draw on clinical revenue. John Park, Casey Dauw, and our former faculty member Humphrey Atiemo (now Program Director at Henry Ford Hospital) accompanied by residents Yooni Yi (UM) and Dan Pucheril (HFH) spent a productive week in Accra. Casey led the team in performing the first successful percutaneous nephrolithotomy in that part of the world. The Korle-Bu Hospital, affiliated with the University of Ghana, is one of the largest teaching hospitals in Africa. John Park will give further details in an upcoming What’s New/Matula Thoughts.

[Casey at bat.]

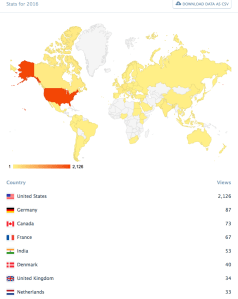

Back here in the USA the economic side of health care is ambiguous. Governmental funding, public policy, regulation, corporatization of the clinical domain, market segmentation, and escalating costs in pharmacologic/technology industries are some factors in the turmoil. Most healthcare industries maintain the public trust and behave admirably in seeking profits and market share – we certainly see this in the companies with whom we deal such as Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Storz, etc.

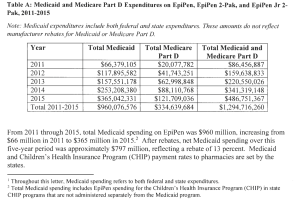

A few egregious actors stand out. The Mylan company’s repackaging of a natural chemical (epinephrine, for which nature holds the patent) with a syringe and needle was a mildly clever gimmick, but creating a monopoly for this lifesaving device and raising the prices for a two-pack from $100 in 2007 to $608 in 2016 is greed beyond the bounds of public acceptance. Mylan’s half price “generic,” offered recently, is a pathetic peace-offering to the public – a generic of a generic is elementary Orwellian Newspeak. [Epinephrine auto-injectors for anaphylaxis. JAMA; 317:313, 2017.] Teva Pharmaceutical was another one of the six drug makers recently sued by 20 state lawmakers on price fixing. These two companies are the largest generic drug makers by market cap. (It must have been awkward for Mylan’s CEO Heather Bresch to justify EpiPen prices because of research and development expenses in testimony to the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee last October.) [M. Krey. Investor’s Business Daily. Mylan launches cheaper EpiPen generic amid drug pricing saga. 12/16/16.] Below: Table A from 10/5/16 letter from CMS Administrator Andrew Slavitt to Senator Ron Wyden regarding Medicaid and Medicare Part D Expenditures on EpiPen products.

Regulation for the public good is essential in a world economy of 7 billion people and GDP of $78 trillion. All businesses exist because of the public trust, going back to the early days of the limited-liability joint-stock company, a story explained in a book called The Company that Julian Wan gave me years ago [John Micklethwait & Adrian Woolridge. Modern Library, NY 2003.] Most US businesses understand their public responsibilities, but uncommon greedy actors erode public trust and diminish the standards for the rest.

Regulation is under attack. It is inevitable that government regulations dampen corporate bottom-lines and short-term economic growth, that is the nature of regulation, but few rational people can deny that serious regulation of highway traffic, airways, nuclear energy, banks, health care, etc. is in the public interest. Offensive governmental regulatory overreach is bound to happen in any complex bureaucracy and should be called out when discovered, but these instances hardly disprove the necessity for regulation by impartial public agencies and civil servants in a healthy democratic society.

By now, in February’s wintry days of cold and snow, the EpiPen story is old news, but we hope that the protective regulatory functions of governmental regulation do not get snowed over or subsumed by corporate world grudges. Like most things in life, balance is essential.

Three.

The world’s deadliest known snowstorm began this February day in 1972, lasting a full week and killing around 4,000 people. The blizzard centered on the city of Ardakan in southern Iran, the region of Shiraz, cultural capital of Iran and known for the eponymous grape. Storyteller Isak Dineson (Baroness Karen Blixen-Finecke, 1885-1962) linked that grape to urology in her short story, The Dreamers: “What is man when you come to think about him, but a minutely set, ingenious machine for turning, with infinite artfulness, the red wine of Shiraz into urine.” Blixen created coherent and compelling stories at a moment’s notice, and told her own life story in the 1934 book Out of Africa, that became a film in 1985 with Meryl Streep and Robert Redford. The complete passage in The Dreamers is particularly intriguing and relevant to urologists.

“ ‘Oh, Lincoln Forstner,’ said the noseless story-teller, ‘what is man, when you come to think upon him, but a minutely set, ingenious machine for turning, with infinite artfulness, the red wine of Shiraz into urine? You may even ask which is the more intense craving and pleasure: to drink or to make water. But in the meantime, what has been done? A song has been composed, a kiss taken, a slanderer slain, a prophet begotten, a righteous judgement given, a joke made…’ ” [Isak Dinesen. Seven Gothic Tales. The Dreamers. 1934, Random House. P. 275.]

Blixen’s choice of Lincoln for the first name of one of the three central characters in her imaginative story is curious, for although it is a well-known surname it is an uncommon given name.

[Karen Blixen and brother Thomas Dineson on her farm in Kenya, c. 1920s. Royal Danish Library.]

Four.

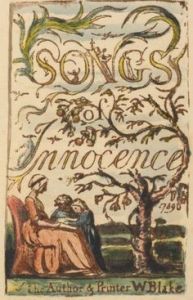

Imagination is the ability to form ideas, images, and sensations without direct sensory input. The practice of medicine, its instruction, and its innovation demand imagination. The imagination to think through the plausibility of things, is inseparable from critical thinking. Observation and reasoning, experience and experiment, are feats of imagination that challenge dogma with new ideas in search of the best truth possible. Such creative thinking is a necessary, but often forgotten piece of the essential skeptical analysis that good physicians and scientists practice and instill in students, residents, fellows, and colleagues.

A recent Lancet article referred to the early American physician Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), who called imagination “… the pioneer of all other faculties.”

“When Rush spoke of imagination, he wasn’t talking about dragons or unicorns, he called that mental faculty fancy, and fancy had no place in medicine. Rather, Rush was talking about how the doctor’s mind gathered observations and experiences, shifting and shaping them until new truths became clear. Memory was a component of this imagination, and understanding resulted from it.” [S. Altschuler. The medical imagination. The Lancet. 388:2230, 2016.]

I’d challenge the claim that no hard line exists between those dragons or unicorns and the new ideas, hypotheses, and truths we hope to discover. Fanciful fiction, visual art, and music enrich mental milieus and provide metaphors, symmetries, dissonances, harmonies, and analogies that make clinical work and science sharper, more multidimensional, and of greater relevance than they would be without the “fancy.” E.O. Wilson infers this in his conclusion to Consilience, a book named for and about the unity of knowledge.

“The search for consilience might seem at first to imprison creativity. The opposite is true. A united system of knowledge is the surest means of identifying the still unexplored domains of reality. It provides a clear map of what is known, and frames the most productive questions for further inquiry. Historians of science often observe that asking the right question is more important than producing the right answer. The right answer to a trivial question is also trivial, but the right question, even when insoluble in exact form, is a guide to major discovery. And so it will ever be in the future excursions of science and imaginative flights of the arts.” [EO Wilson. Consilience. Alfred A. Knopf. New York.]

Creativity can also spring from irrational thought as a song in the new film La La Land suggests. Audition (The fools who dream) sung by Emma Stone: “A bit of madness is key, to give us new colors to see. Who knows where it will lead us and that’s why they need us.” Human exploration of reality requires consilience of all the tools we can muster, including scientific knowledge, historical facts, stories, and imaginative fancy.

Five.

When you read a story or experience visual art you may discover something new to which your brain can connect and that will illuminate other stuff in your brain at that moment or later on in reflections, dreams, or sudden denouements. Those connections provoke imagination, test reality, and elicit wisdom that affects your world view and your work. Insight and inspiration from art provide limitless opportunities in the practice, teaching, or investigation of medical care. The story of British pediatrician Harry Angelman (1915-1966) offers a minute and excellent example of illuminating connection.

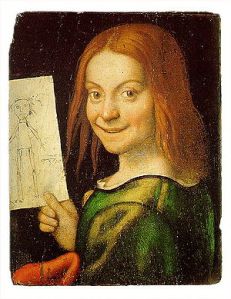

“It was purely by chance that nearly thirty years ago (e.g., circa 1964) three handicapped children were admitted at various times to my children’s ward in England. They had a variety of disabilities and although at first sight they seemed to be suffering from different conditions I felt that there was a common cause for their illness. The diagnosis was purely a clinical one because in spite of technical investigations which today are more refined I was unable to establish scientific proof that the three children all had the same handicap. In view of this I hesitated to write about them in the medical journals. However, when on holiday in Italy I happened to see an oil painting in the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona called . . . a Boy with a Puppet. The boy’s laughing face and the fact that my patients exhibited jerky movements gave me the idea of writing an article about the three children with a title of Puppet Children. It was not a name that pleased all parents but it served as a means of combining the three little patients into a single group. Later the name was changed to Angelman syndrome. This article was published in 1965 and after some initial interest lay almost forgotten until the early eighties.” [Quotation from Charles Williams. Harry Angelman and the History of AS. Stay informed. USA: Angelman Syndrome Foundation. 2011.]

Giovanni Francesco Caroto (1480-1555), the Renaissance painter in Verona, created the Portrait of a Child with a Drawing and the circumstances of the subject will probably never come to light. It may well be a coincidence that the picture resembled the patients that provoked Angelman’s curiosity.

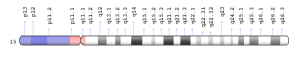

[Chromosome 15]

Deletion or inactivation of genes on maternal chromosome 15 with silencing of the corresponding normal paternal chromosome is responsible for AS. Similar genomic imprinting, but with deletion or inactivation of paternal genes and silencing on the maternal side happens in Prader-Willi syndrome, that shows up more often in our pediatric urology clinics. These two conditions along with Beckwith-Wiedemann and Silver-Russell syndromes were early reported instances of human imprinting disorders. An excellent update on these conditions appeared last month in Science. [J. Cousin-Frankel. Fateful Imprints. Science. 355:122-125, 2017]

Six.

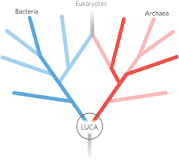

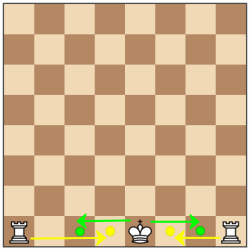

New residents. We just matched our new cohort of PGY1s, a stage of medical education once called internship, that starts each July to initiate the transition of medical students into specialists. The medical student is the last universal common ancestor in the evolution of a medical specialist. About 150 areas of focused practice (per American Board of Medical Specialties) are available to freshly minted MDs and those last universal common ancestors in medicine evolve into the new species of their chosen specialties during their residencies.

This educational experience is a primary reason we exist as a Department of Urology. The UMMS was formed to produce the next generation of physicians for the State of Michigan in 1850 when this mission required 2 years of medical school lectures to achieve the MD necessary to practice medicine. The medical school then needed only 5 faculty and 2 departments (Medicine as well as Surgery and Anatomy) to provide that education. Today’s world of specialty medicine requires 4 years of medical school (with lectures, laboratory work, and clinical experience) as well as graduate medical education in one of 100 areas of specialty training offered here in Ann Arbor. Our medical school faculty numbers 2500 in 30 departments. We educate, at any moment, about twice as many residents in specialties as medical students – and the period of residency training may be more than twice as long as medical school itself.

New members of the UM Urology family are: Juan Andino with BS, MBA, and MD degrees from UM; Chris Tam with BS from UC San Diego and MD from the University of Iowa; Robert Wang with BA and MD degrees from Washington University in St. Louis; and Colton Walker with BS from Stanford and MD from Louisiana State University in New Orleans. Who knows where they will lead us?

Seven.

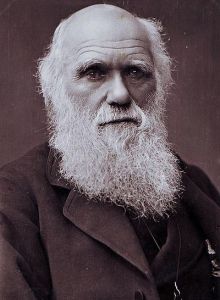

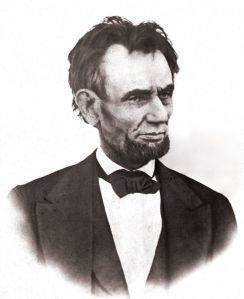

Darwin & Lincoln’s birth, on the same day in the same year, was the wonderful coincidence of February 12, 1809. Two more different circumstances for those neonates would be difficult to imagine although both families had roots in England. Both men had big imaginations that changed the world in positive ways that endure today. Darwin arrived in the center of the civilized world, Shrewsbury England, to a prosperous family. His grandfather, Dr. Erasmus Darwin, was one of the great thinkers of his time and his father Dr. Robert Darwin was a successful physician. The house where Charles Darwin was born was distinguished enough to have a name, The Mount. Abraham Lincoln was born in a small primitive cabin, now long gone, on the Sinking Spring farm on the western periphery of a nation barely 33 years in existence. The nearest town, Hodgenville, didn’t even get its name until 1826, long after the Lincoln family, short on money and education, had moved on.

[Above: Photo by Herbert Barraud, last known picture of Darwin. 1882. Huntington Library. Below: Last known high-quality Lincoln photo, March 6, 1865. Library of Congress.]

Darwin’s idea, The Origin of Species, contained the belief that species couldn’t breed with different species. The classic example of reproductive isolation that many of us recall from childhood was the mule, the result of a donkey and horse breaking the species barrier recreationally, but the resulting progeny was sterile and incapable of creating a further bloodline. That belief in a barrier to interbreeding, or hybridization as biologists term the process, has fallen away in the new era of genomic information. The Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in the Homo sapiens genome is a rather intimate example of species interbreeding. It turns out that hybridization has played an important role in evolution throughout most kingdoms of life. The mule is joined by the liger (lion/tiger), Hawaiian duck (Mallard/Laysan duck), red wolf (coyote/gray wolf), and pizzly (polar/brown bear). Domestic dog and wolf interbreeding has given wolves a variant immune protein gene, β-defensin, that conveys a distinctive black pelt and improved canine distemper resistance to wolf/dog hybrids and their descendants. [Elizabeth Pennisi. Shaking up the tree of life. Science: 354:817-821, 2016.] In a practical sense for our work in healthcare, bacterial swapping of DNA presents great challenges. Darwin recognized a mighty force – nearly as mysterious and pervasive as gravity – that crops up way beyond biology. Even in social ebbs and flows of life, Darwinian forces are at play, for surely they have made markets, politics, and academia increasingly creative.

Eight.

LUCA. Central to the multiple facets of our interests and knowledge as clinicians, surgeons, and urologists, we are ultimately biologists. In that spirit, the mystery of how life began on Earth is an irresistible intellectual puzzle and if you align to the Darwinian line of the speculation the concept of a very simple common ancestor holds traction.

Such a single cell, bacterial-like organism would have begat the three great domains of life: archaea, bacteria, and later the eukaryotes. Of the 6 million protein-coding genes in DNA data banks, William Martin et al at Heinrich Heine University in Dusseldorf speculated that 355 were present in that most primitive of ancestors, called the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA). These probably originated around volcanic sea vents that supplied just the right conditions. Whether or not LUCA came from sea vents, warm ponds, or other environments should become clearer as biologists dig deeper into our roots. LUCA might have looked like any of the archaea and bacteria we recognize today with stiff walled rods or cocci. More complex shapes required the flexible cell walls that came later with eukaryotes. LUCA probably existed as an anaerobe in a vent-like hydrothermal geochemical setting and was based upon 355 genes according to a paper from the Institute of Molecular Evolution at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf.

[Figure from MC Weiss, FL Sousa, N Mrnjavac et al. The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor. Nature Microbiology. 1, Article number 16116, 2016.]

Much has happened since LUCA. Given the Darwinian trials of variation by error in the face of minor and gross environmental challenges over millions of millennia, new species developed in fits and starts. The Cambrian explosion of new creatures was one of many responses of speciation to planetary change. We humans seem to be at the far opposite end of the phylogenic spectrum from LUCA. Our complexity is not just a matter of our biology and our cerebral skills, but no less a matter of the social nuances that elaborate the human condition.

Nine.

A Fortunate Man. The classic study of an English general practitioner in the 1960s, alluded to on these pages last year sharpened my perspective as a physician. [John Berger, A Fortunate Man, Random House, NY 1967.] The ancient perspective of healthcare, documented since medical recipes in ancient early Egyptian papyri and Hippocratic writings, was a matter of dualities: one patient-one physician, one problem-one solution, and one teacher-one student. This changed in the past century due to medical specialties and technology that have introduced unmeasurable complexity. Patient care and medical education are no longer two-body problems, but are now part of a multidimensional healthcare matrix.

Even that multidimensional professional matrix is dwarfed by the complexity of patients with their own multidimensional physical, mental, familial, social, economic, political, and environmental comorbidities. You might lump all these comorbidities together and simply call them “the human condition” that Berger probed in A Fortunate Man, hinting that we really have little sense of what our patients are all about. However, as we practice our art, we become better at understanding the holograms of the patients as they present themselves in our clinics even in the short time frames at hand and the insistence of electronic health records and economics that force us to default to two-body problems (augmented with a few clever comorbidities that can permit a more realistic billing code).

Berger died last month (January 2) at 90 in the Parisian suburb where he lived. I didn’t know much about him since I read his book just last year (and I wish I could remember who told me to read it). Berger (pronounced BER-jer,) was known as a “provocative art critic” in the obituary by Randy Kennedy that included this example:

“He was a champion of realism during the rise of Abstract Expressionism, and he took on giants like Jackson Pollock, whom he criticized as a talented failure for being unable to ‘see or think beyond the decadence of the culture to which he belongs.’” [Kennedy. New York Times Tuesday January 3, 2017.]

The obituary ran for three columns and mentioned a number of Berger’s books, but not A Fortunate Man.

Ten.

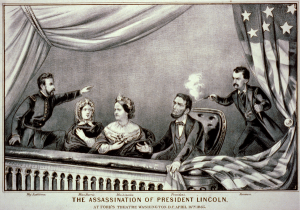

That other birthday celebrant of February 12, 1819, would also have been 198 years old this month. Human biology at its best wouldn’t have given Lincoln that chance, but it was political extremism that cut him down short of his potential fourscore and ten years. While Darwin’s ancestors provided more than a hint of greatness for their descendent, Lincoln’s ancestry offered no such clue, but his insatiable drive for education and personal distinction contrasted remarkably with the rest of his family. His improbable success in law and politics leveraged his even more unlikely ascent to the presidency of the United States. No one could have predicted that his ultimate comorbidity would have been an actor with a Philadelphia Derringer at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865.

[Top: Currier & Ives print of assassination April 14, 1865. Middle: The actual Derringer. Bottom: 0.41-caliber Rimfire cartridge.]

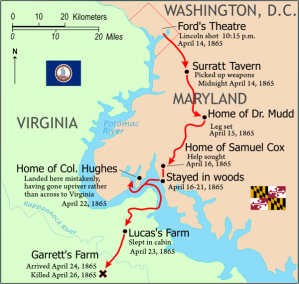

Lincoln’s assassin jumped to the stage and escaped on a horse waiting near the backstage door. The following day he stopped near Beantown, Maryland (now Waldorf) seeking treatment at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, an acquaintance, for a broken left fibula. Mudd cut off Booth’s boot, splinted the leg, provided a shoe, and arranged for a local carpenter to make a pair of crutches. After catching some sleep at the doctor’s house Booth travelled on to Virginia where he was caught and killed on April 26. Mudd was arrested, charged with conspiracy, and imprisoned at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. He tried to escape once, but became a good prisoner and was released after pardon by President Andrew Johnson on March 8, 1869. Mudd returned home to Maryland where he lived until January 10, 1883 dying of pneumonia at 49 years of age. Mudd’s grandson, Dr. Richard Mudd, unsuccessfully petitioned a number of presidents (Carter and Reagan) and also failed in other avenues to clear the family name of the stigma of aiding Booth. The family name remains Mudd.

[Booth escape route. Wikimedia Commons. Courtesy, National Park Service.]

Our world has changed enormously since Lincoln’s time. The American democracy is better, healthcare is more effective, and the Earth even when viewed from far out in our solar system looks amazingly different (below); Edison’s electrical illumination, invented in 1880, has impacted both the visible planet and environment due to the fossil fuel consumption for those lights.

A short book on Darwin and Lincoln, Angels and Ages by Adam Gopnik [Alfred A. Knopf, NY 2009] noted:

“What all the first modern artists, from Whitman to van Gogh, have believed is that, for whatever reason, and however it came to be, we are capable of witnessing and experiencing the world as more than the sum of our instincts and appetites. Our altruism is not simply our appetites compounded; our appetites are not simply our altruism exposed. ‘Reason … must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense,’ Lincoln said, and reason alone can point us to its limits. We can argue about anything, even about the nature and meaning of our mysticisms. [Kenneth] Clark called our liberal faith ‘heroic materialism’ and said it wouldn’t be enough. Human materialism or mystical materialism, is closer to it, and it remains the best we have. Intimations of the numinous may begin and end in us, but they are as real as descriptions of the natural; Sunday feelings are as real as Monday facts. On this point, Darwin and Lincoln, along with all the other poets of modern life, would have agreed. There is more to a man than the breath in his body, if only on the hat on his head and the hope in his heart.”

[Footnotes: Numinous = inspiriting spiritual or awe-inspiring emotions. Mystical = having spiritual meaning neither apparent to sense or obvious to intelligence.]

David A. Bloom

University of Michigan, Department of Urology, Ann Arbor