Matula Thoughts – August 5, 2016

Summertime field notes, superheroes, and retrograde thoughts.

3975 words

Patient experience. Walking through the Art Fairs last month after great lectures from visiting professors, my thoughts wandered to Matula Thoughts/What’s New, this electronic communication that has become my habit for the past 16 years. It may be presumptuous to think that anyone would spend 20 minutes or more reading this monthly packet approaching 4000 words. Certainly, UM urology residents and faculty are too busy to give this more than a glance, and that’s OK by me. Of the 10 items usually offered I’d be happy if most folks just skimmed them and perhaps discovered one of enough interest to read in detail. Conversely, some alumni and friends hold me to account for each word and fact, and they are enough for me to know that this communication (What’s New email and Matula Thoughts website) is more than my whistling in the wind.

One.

Art & medicine. Luke Fildes’s painting, The Doctor, shown here last month, deserves further consideration in the afterglow of Don Nakayama’s Chang Lecture on Art & Medicine. [1892, Tate Gallery]. The duality of the doctor-patient relationship, ever so central to our profession, has gotten complicated by changes in technology, growth of subspecialties, necessity of teams and systems, and the sheer expense of modern healthcare. As Fildes shows, medical relationships in the pediatric world extend beyond twosomes and this actually pertains for all ages, since no one is an island. That nuance notwithstanding, the patient experience through the ages and into the complexity of today remains the central organizing principle of medicine.

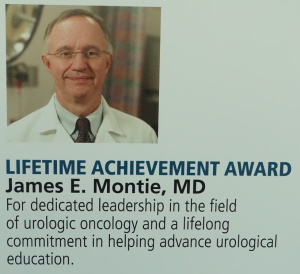

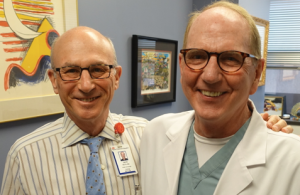

[Dr. Chang & Don Nakayama]

An article in JAMA recently explored the patient experience via the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (HCAHPS) Survey. Delivered to random samples of newly discharged adult inpatients, the 32 items queried are measurements of patient experience that parlay into hospital quality comparisons and impact payments. [Tefera, Lehrman, Conway. Measurement of the patient experience. JAMA 315:2167, 2016]

It is unfortunate that health care systems and professional organizations hadn’t previously focused similar attention on patient experience and only now are compelled to investigate and improve it by the survey. We may chafe and groan at HCAHPS, but it reflects well on representational government working on behalf of its smallest and most important common denominator – individual people.

Everyone deserves a good experience when they need health care whether for childbirth, vaccination, otitis, UTI, injury, other ailments and disabilities, or the end of life. If for nothing more than “the golden rule” all of us in health care should constantly fine-tune our work to make patient care experiences uniformly excellent because, after all, we all become patients at points in life. The individual patient care experience is the essential deliverable of medicine and the epicenter of academic health care centers from the first day of medical school to the last day of practice, after which we all surely will become patients again.

Two.

Educating doctors. Last week’s White Coat Ceremony was the first day of medical school class for Michigan’s of 2020. Deans Rajesh Mangulkar and Steven Gay with their admissions team assembled this splendid 170th UMMS class. Unifying ceremonies are important cultural practices and this one is an exciting milestone for students and a pleasant occasion for the faculty who will be teaching the concepts, skills, and professionalism of medicine. Families in attendance held restless infants, took pictures, and applauded daughters and sons. A “doctor in the family,” for most of the audience, happens once in a blue moon, a rare circumstance of joy, and certainly evidence of success and luck in parenting. The attentive audience for the 172 new students entertained only rare social media diversions. Julian Wan represented our department on stage.

Dee Fenner’s keynote talk resonated deeply. She described her career as a female pelvic surgeon and its impact on patients and on herself. Dee talked about the symbolism of the white coat and skewered today’s hype about “personalized medicine”, saying that medicine is always rightly personalized; our ability to tailor health care to the individual genome is just a matter of using better tools. Alumni president (MCAS) Louito Edje said: “This medical school is the birthplace of experts. You have just taken the first step toward becoming one of those experts.” She recommended cultivation of three fundamental attitudes to knowledge: humility, adaptability, and generosity. Students then came to the stage and announced their names and origins before getting “cloaked.”

The ceremony passes quickly, but is long remembered. Students shortly immerse in intense learning, although medical school is kinder today with less grading, rare attrition, and greater attention to personal success and matters of team work.

My favorite “new medical student story” concerns the late Horace Davenport. He had retired before I arrived in Ann Arbor, but remained active in the medical students’ Victor Vaughn Society that met monthly at a faculty home for a talk over dinner. Davenport, an international expert in physiology, was a superb and fearsome teacher as one student, Joseph J. Weiss (UMMS 1961), recalled from the fall of 1957.

“In our first physiology lecture Dr. Horace Davenport grabbed our attention by announcing that the first person to answer his question correctly would receive an ‘A’ in physiology and be exempt from any examinations or attendance. The question was: ‘What happened in 1623? The context implied an event of significant impact to human knowledge. After a long pause the amphitheater echoed with answers: the discovery of America, the landing of the pilgrim fathers, the death of Leonardo da Vinci. Then Nancy Zuzow called out: ‘The publication of William Harvey’s The Heart and its Circulation’. There was sudden silence. She must be right. How clever of her. Of course a physiologist would see this landmark publication as an event to which we should give homage. Who would have thought that Nancy was so smart? Even Dr. Davenport was impressed. He asked her to stand, and acknowledged that she had provided the first intelligent response. ‘However,’ he noted, ‘that publication occurred in 1628.’ No one could follow up up on Nancy’s response. Dr. Davenport looked around the room, sensed our ignorance, realized we had nothing more to offer, and then said: ‘1623 was the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio.’ He announced that we would now move on and ‘return to our roles as attendants at the gas station of life”,’ and began his first in a series of three lectures on the ABC of Acid-Base Chemistry.” [Medicine at Michigan, Fall, 2000. Weiss, a rheumatologist who practiced in Livonia, passed away in October 2015. Zuzow died in 1964, while chief resident in OB GYN at St. Joseph Mercy, of a cerebral hemorrhage.]

Three.

New Perspectives. Visiting professors bring different perspectives and last month the Department of Urology initiated its new academic season with several superb visitors. Distinguished pediatric surgeon Don Nakayama gave our 10th annual Chang Lecture on Art and Medicine on the Diego Rivera Detroit Industry Murals. [Below: full house for Nakayama at Ford Auditorium]

I’ve been asked what relevance an art and medicine lecture has for a urology department’s faculty, residents, staff, alumni, and friends. Davenport would not have questioned the matter. This year, in particular, the lecture made perfect sense with Don’s discussion of what can now be called the orchiectomy panel in the Detroit Institute of Arts murals. Hundreds of thousands of people have viewed this work since 1933, including the surgical panel that art historians labeled “brain surgery” – a description unchallenged until Don revealed the scene represented an orchiectomy. His Chang Lecture explained the logic of Rivera’s choice.

[Top: Caleb & Sandy Nelson; Middle: Bart & Amy Grossman, Bottom: George Drach]

The day after the Chang Lecture, Caleb Nelson (Nesbit 2003) from Boston Children’s Hospital and Bart Grossman (Nesbit 1977) of MD Anderson Hospital in Houston delivered superb Duckett and Lapides Lectures. Caleb discussed the important NIH vesicoureteral reflux study while Bart brought us up to date on bladder cancer, greatly expanding my knowledge regarding the rapid advances in its pathogenesis and therapy. George Drach from the University of Pennsylvania provided a clear and instructive update on Medicaid coverage for children. Concurrent staff training went well thanks to those who stayed behind from this yearly academic morning to manage phones, clinics, and inevitable emergencies.

[Above: Lapides Lecture, Danto Auditorium]

Four.

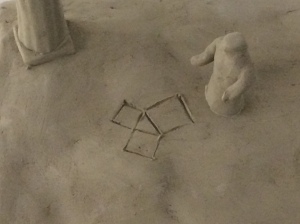

Observation & reasoning. Don Coffey, legendary scientist and Johns Hopkins urology scholar, retired recently. Among his numerous memorable sayings he sometimes mentioned an old southern phrase: “if you see a turtle on a fencepost, it ain’t no coincidence.” A tortoise on a post isn’t some random situation that happens once in a blue moon, it is more likely the result of a purposeful and explainable action. (Of course, it is also not a nice thing.) Coffey was arguing for the importance of reflective and critical thinking as we stumble through the world and try to make sense of it, whether on a summertime pasture, in an art gallery, or in a laboratory examining Western blots.

[Above: tortoise sculpture on post. Mike Hommel’s yard AA, summer, 2016. Below: Coffey]

Richard Feynman (above), Nobel Laureate Physicist, offered a related metaphor.

“What do we mean by ‘understanding’ something? We can imagine that this complicated array of moving things which constitutes ‘the world’ is something like a great chess game being played by the gods, and we are observers of the game. We do not know what the rules of the game are; all we are allowed to do is to watch the playing. Of course if we watch long enough we may eventually catch on to a few of the rules… (Every once in a while something like castling is going on that we still do not understand).” [RP Feynman. Six Easy Pieces. 1995 Addison-Wesley. P.24]

Observation, reasoning, and experimentation are the fundamental parts of the scientific method that allows us to figure things out. Feynman’s castling allusion is brilliant.

[EO Wilson at UM LSI Convocation 2004]

E.O. Wilson went further with his thoughts on consilience, the unity of knowledge.

“You will see at once why I believe that the Enlightenment thinkers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries got it mostly right the first time. The assumptions they made of a lawful material world, the intrinsic unity of knowledge, and the potential of indefinite human progress are the ones we still take most readily into our hearts, suffer without, and find maximally rewarding through intellectual advance. The greatest enterprise of the mind has always been and always will be the attempted linkage of the sciences and humanities. The ongoing fragmentation of knowledge and resulting chaos in philosophy are not reflections of the real world, but artifacts of scholarship. The propositions of the original Enlightenment are increasing favored by objective evidence, especially from the natural sciences.” [Wilson. Consilience. P. 8. 1998]

Five.

Superheros. Somewhat to our cultural disadvantage our brains are hardwired to favor physical performance, entertainment, and appearances over intellectual leaps of greatness. We celebrate actors, athletes, politicians, musicians, and cartoons far more than great intellects. Worse, intellectuals in many periods of history were deliberately purged.

Coffey, Feynman, and Wilson are real superheroes of our time. Their ideas have been hugely consequential and they individually are role models of character and intellect. Another name to add to the superhero list is Tu Youyou (屠呦呦). My friend Marston Linehan first alerted me to her incredible story and discovery of artemisinin. It is also a story of how the better nature of humanity is subject to the dark side of our species and the nations we let govern us.

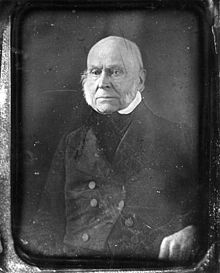

Born in Ningbo, Zhejiang, China in 1930 Tu Youyou attended Peking University Medical School, developed an interest in pharmacology, and after graduation in 1955 began research at the Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Beijing. This was a tricky time to be a scientist in Maoist China. Ruling authorities favored peasants as the essential revolutionary class and in May 1966, the Cultural Revolution launched violent class struggle with persecution of the “bourgeois and revisionist” elements. The Nine Black Categories (landlords, rich farmers, anti-revolutionaries, malcontents, right-wingers, traitors, spies, presumed capitalists, and intellectuals) were cruelly relocated to work or forage in the countryside while neo-revolutionaries disestablished the national status quo.

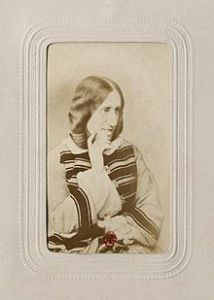

In 1967 as North Vietnamese troops contended in jungle combat with US forces, chloroquine-resistant malaria was taking a heavy toll on both sides. Mao Zedong launched a secret drug discovery project, Project 523, that Tu Youyou joined while her husband, a metallurgical engineer, was banished to the countryside and their daughter was placed in a Beijing nursery. Screening traditional Chinese herbs for anti-plasmodial effects Tu found Artemisia (sweet wormwood or quinghao) mentioned in a text 1,600 years old, called Emergency Prescriptions Kept Up One’s Sleeve (in translation). She led a team that developed an artemisinin-based drug combination, publishing the work anonymously in 1977, the year after the revolution had largely wound down and only in 1981 personally presented the work to World Health Organization (WHO). Artemisinin regimens are listed in the WHO catalog of “Essential Medicines.” Tu won the 2011 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award and in 2015 the Nobel Prize In Physiology or Medicine for this work.

[Above: Artemisia annua. Below: Tu Youyou with teacher Lou Zhicen in 1951]

Six.

It may be a human conceit to think of ourselves as the singular species on Earth capable of self-improvement. Considering the impact of Coffey, Feynman, Wilson, and Tu among other intellectual superheroes, imagination at their levels seems a rarity in the universe. Yet, any sentient creature wants to improve its comfort as well as its immediate and future prospects, for who is to say that a whale, a dolphin, a gorilla, or an elephant cannot somehow imagine a more comfortable, happier, or otherwise better tomorrow? In anticipation of another day, birds make nests, ants make tunnels, and bees make hives.

We humans have extraordinary powers of language, skill (with our cherished opposable thumbs), and imagination that provide unprecedented capacity to improve ourselves. Accordingly we easily imagine ourselves in better situations, whether physically, materially, intellectually, or morally, and as it is said, if we can imagine something we probably can create it.

Imagination of a better tomorrow is part of the drive for change as we consider our political future, although this can be risky. The intoxicating saying out with the old and in with the new has led to such things as the United States of America in 1776 or the Maastricht Treaty and European Union in 1992. Change, however, does not always produce happy alternatives, as evidenced by the Third Reich, the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the Arab Spring, or Venezuela’s Chavez era. Disestablishment does not predictably improve life for most people. The human construct, at its best and most creative, rests on a fragile establishment of geopolitical, economic, and environmental stability. The status quo that has been established may be imperfect, but is disestablished only at considerable risk.

Representational government and cosmopolitan society seem to be the best-case scenario for what might be called the human experiment wherein various factions of a diverse population come together to create a just social agenda and build a better tomorrow. The threat to this utopian scenario comes from factionalisms and tribalisms that insert narrow self -interests and litmus tests for cooperation into any consensus for agenda. We see this in the mid-east, in the European Zone, and in American presidential election cycles. Generally ignored or forgotten by competing factions and litmus-testers is the worst-case scenario of civil collapse. We experienced limited episodes of this in two World Wars, southeastern Asian catastrophes, central African genocides, Yugoslavia’s dissolution, and the collapse of Syria to name some instances. However sturdy we think human civilization may be, it is only a thin veneer in a random and dangerous universe. Civil implosions of one sort or another occur intermittently in complex societies, however we must become better at predicting them, circumventing them, and most importantly preventing their dissemination. Their catastrophic nature surpasses any sectarian interests or individual beliefs beyond the survival of civilization itself.

Seven.

The Blue Moon, mentioned earlier, is a picturesque metaphor for an uncommon event. It’s actually not random, inasmuch as a blue moon is a second full moon in a given month (or other calendar period), so the next one can be accurately predicted. Since a full moon occurs about every 29.5 days, on the uncommon occasions it appears at the very beginning of a month, there is a chance of Blue Moon within that same month. The next Blue Moon we can expect will be January 31, 2018.

The song is a familiar one. It was originally “MGM song #225 Prayer (Oh Lord Make Me a Movie Star)” by Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart in 1933. Other lyrics were applied, but none stuck until Hart wrote Blue Moon in 1935.

Nothing is visually different between blue moons or any other full moons. I took this picture (above) of a nearly full moon this June after some trial and error. A full moon is a beautiful thing and can’t help but give anyone a sense of the small individual human context. Friend and colleague Philip Ransley, now working mainly in Pakistan, spent much of his career aligning his visiting professorships around the world with lunar eclipses and lugging telescopes and cameras along with his pediatric urology slides. Receiving the Pediatric Urology Medal in 2001, barely a month after the tragic event of September 11, 2001, he spoke on lunar-solar rhythms, shadows, and their relationship to the human narrative: “… I would like to lead you into my other life, a life dominated by gravity and its sales rep, time. It has been brought home to us very forcibly how gravity rules our lives and how it governs everything that moves in the universe.” [Ransley. Chasing the moon’s shadow J. Urol. 168:1671, 2002]

[PG Ransley c. 2005]

Ransley is currently working in Karachi, Pakistan at the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, the largest center of urology, nephrology, and renal transplantation in SE Asia. The pediatric urology unit at SIUT is named The Philip G. Ransley Department. [Sultan, S. Front. Pediatr. 2:88, 2014]

Eight.

Ruthless foragers. Earlier this summer a friend and colleague from Boston Children’s Hospital, David Diamond, brought me along for a bluefish excursion off of Cape Cod. These formidable eating machines travel up and down the Atlantic coast foraging for smaller fish. Like many other targets of human consumption, blue fish are not as plentiful as they once were, although they are hardly endangered today.

[From Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission]

Just as we label ourselves Homo sapiens, the bluefish are Pomatomus saltatrix. Both, coincidentally, were named by Linnaeus, the botanist who got his start as a proto-urologist, treating venereal disease in mid 18th century Stockholm. His binomial classification system (Genus, species) is the basis of zoological conversation, although genomic reclassification will upend many assumptions. Also like us, the bluefish is the only extant species of its genus – Pomatomidae for the fish and Hominidae for us. Thus we are both either the end of a biologic family line or the beginning of something new. Our fellow hominids, such as Neanderthals, Denisovans, or Homo floresiensis didn’t last much beyond 30,000 years ago, although they left some of their DNA with us. It may be a long shot, but I hope H. sapiens can go another 30,000 years.

[Bove: ruthless foragers]

Like us, Pomatomus saltatrix are ruthless foragers, eating voraciously well past the point of hunger. Their teeth are hard and sharp, reminding me of the piranha I caught on an unexpected visit to the Hato Piñero Jungle when attending a neurogenic bladder meeting in Venezuela some 20 years ago. Lest you think me a serious fisherman, I disclose there’ve not been many fish in between these two.

[one of 4 piranha geni (Pristobrycon, Pygocentrus, Pygopristis, & Serrasalmus that include over 60 species]

Linnaeus gave bluefish a scientific name in 1754, describing the scar-like line on the gill cover and feeding frenzy behavior (tomos for cut and poma for cover; saltatrix for jumper, as in somersault). I learned this from the book Blues, by author John Hersey (1914-1993), who was better known for his Pulitzer novel, A Bell for Adano (1944) or his other nonfiction book, Hiroshima (1946). [Below: Hersey]

Michigan trivia: Hersey lettered in football at Yale where he was coached by UM alumnus Gerald Ford who was an assistant coach in football and boxing for several years before admission to Yale’s law school. Hersey became a journalist after college and graduate school in Cambridge. In the winter of 1945-46 while in Japan reporting for The New Yorker on the reconstruction after the war he met a Jesuit missionary who survived the Hiroshima bomb, and through him and other survivors put together an unforgettable narrative of the event. The bluefish story came later (1987).

Nine.

Today & tomorrow. Today is the start of the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil where 500,000 visitors are expected, presumably well covered and armed with insect repellent due to fears of Zika, an arbovirus related to dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and West Nile viruses.

Tomorrow is a sobering anniversary. I was 11 days old, on August 6, 1945, when, at 8:15 AM, a burst of energy 600 meters above the Aioi Bridge in Hiroshima, Japan incinerated half the city’s population of 340,000 people. Don Nakayama wrote a compelling article on the surgeons of Hiroshima at Ground Zero, detailing individual stories of professional heroism. [D. Nakayama. Surgeons at Ground Zero of the Atomic Age. J. Surg. Ed. 71:444, 2014] We reflect on Hiroshima (and Nagasaki) not only to honor the fallen innocents and to re-learn the terrible consequences of armed conflict, but also to recognize how close we are to self-extermination. A new book by former Secretary of Defense, William Perry, makes this possibility very clear, showing how much closer we came to that brink during the Cuban Missile Crisis. [Perry. My Journey at the Nuclear Brink. Stanford University Press. 2016]

Ten.

Self-determination vs. self-termination. Life, and our species in particular, is far less common in the known universe than Blue Moons, it might be said, although those moons actually are mere artifacts of calendars and imagination. Art and medicine are distinguishing features of our species, Homo sapiens 1.0. The ancient cave dwelling illustrations of handprints on the walls and galloping horses, are evidence of our primeval need to express ourselves by making images. The need to care for each other (“medicine” is not quite the right word) is an extension from the fact that we are perhaps the only species that needs direct physical assistance to deliver our progeny. If our species is to have a future version (Homo sapiens 2.0) we will have to check ourselves pretty quickly before we terminate ourselves, through war and genocide, consumption of planetary resources, or degradation of the environment. While representational government, nationally and internationally, may be our best hope to prevent termination we will have to represent ourselves a lot better. That’s a fact whether here in Ann Arbor, in Washington DC, in China, Africa, Asia, or Europe.

Tribalism resonates with many deep human needs and it has gotten our species along this far, but H. sapiens 2.0 will have to make the jump from tribalist behavior to global cosmopolitanism. Sebastian Junger, a well-known war journalist, has written a compelling book that explores the human need for a sense of community that he describes by the title, Tribe. While we need better sense of community in complex cosmopolitan society, we cannot accept primitive tribalism, sectarianism, or nativism of exclusivity that exacerbate conflict among the “isms.” Tribalism cannot create an optimal or even a good human future whether the version is Brexist or ISIS, paths retrograde to human progress and the wellbeing of humanity in general.

[Girl with Pearl Earing, Vermeer, c. 1665, & viewers at Mauritius Museum, The Hague]

Reflections on art and medicine lead to cosmopolitan and humanitarian thought and behavior. Humanistic reflection, shared broadly, should track us more closely to a utopian scenario, rather than to catastrophe that is only a random contingency away.

[Anatomy Lesson of Nicolaes Tulp. Rembrandt, 1632. Mauritius Museum, The Hague]

Thank you for reading our Matula Thoughts.

David A. Bloom

University of Michigan, Department of Urology, Ann Arbor