Politics, nutcrackers, and earthly delights

3799 words

One.

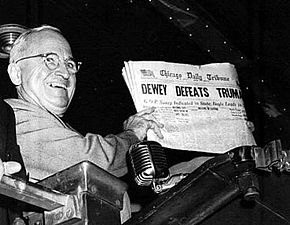

This has been a year of political surprises with Brexit, the Columbian failure to reconcile with FARC, and the American presidential election. The weekend after our election I happened to be at the Fourth Quinquennial John W. Duckett Festschrift at the Union League of Philadelphia. This venerable institution was founded in 1862 as a patriotic society to support the policies of Abraham Lincoln, whose ideas seem so obvious and mainstream today, but they split the United States nearly permanently at that time. In a Union League reading room you see our friend and colleague George Drach contemplating the meaning of the election for healthcare. Just this past summer George spoke at our Duckett/Lapides Symposium on the implications of the MACRA law, passed earlier this spring with strong bipartisan support. Whether or not the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and MACRA disappear, healthcare policy, regulation, and economics are going to get evermore contentious and confusing. Politics may be easy to distain, but they surround us and shape our lives. This milestone day, December 2, is worth recalling for two examples of politics and ideologies that led nations and people sadly astray.

First example: red scares. The Cold War, following WWII, instilled legitimate anxiety over the spread of communism in the West where scoundrels capitalized on that fear and created the Second Red Scare (1947-57). A First Red Scare (1919) followed WWI and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Both phenomena occurred during times of patriotic intensity and exploited fears of communism. The second scare lasted far longer than the first and came to be known as McCarthyism after its central figure Joseph McCarthy, US Senator from Wisconsin.

[Above: Herblock cartoon March 29, 1950 Washington Post, introducing the term McCarthyism.] Paranoia crossed the United States from Washington to Hollywood and left its effects in Ann Arbor, where 3 faculty members were dismissed by the University for refusing to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Mark Nickerson (UMMS Pharmacology), H. Chandler Davis (UM Mathematics), and Clement Markert (UM Biology), suspected of membership in the Communist Party, were called to Lansing on May 10, 1954 to testify before an HUAC sub-committee. The professors refused to answer certain questions, claiming Fifth Amendment privilege, and UM President Harlan Hatcher promptly suspended them pending a faculty inquiry related to “intellectual integrity.” Nickerson was fired out of concern that he was damaging the reputation of the Medical School and University. He went on to a distinguished career in Canada. Davis was also fired and later served jail time for contempt of Congress. Markert was retained but left UM soon thereafter. While this breech of their civil rights passed public muster in the Red Scare fervor, the breech of their tenure rights (Regents bylaw 509) tripped up the university and caused an academic firestorm. The American Association of University Professors would later ask the UM to make “a significant gesture of reconciliation” and that became the annual Davis, Markert, Nickerson Lecture on Academic and Intellectual Freedom. [James Tobin. Seeing Red. Medicine at Michigan Spring, 2009; 11:14-15] That second Red Scare began to wind down later in 1954 on this day, December 2, when the United States Senate voted 65 to 22 to censure McCarthy for “conduct that tends to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute.”

Second example: smoke and mirrors. On this day in 1961 Fidel Castro, in a nationally broadcast speech, announced that Cuba would adopt Communism, surprising us in the north and setting off a chain of events with the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year that nearly brought the world to nuclear confrontation. A recent book by former Secretary of Defense William Perry (My Journey at the Nuclear Brink – mentioned here a few months back) offers a frightening account of that time and a more frightening preview of the world ahead of us now. While Castro’s iron grip endured for a half century his ideological experiment failed and he died just 7 days ago. Venezuela under Hugo Chavez tried to reprise the Cuban experiment, but that too didn’t turn out well for its people. Chavez died in 2013 after treatment in Cuba for unspecified malignancy. Both dictators rode waves of populism in their countries, where celebrity ideology support them even to this day, in spite of the economic and social disintegration they left behind, showing once again that populism usually turns out poorly for the populace at the end of the day. [Picture above: Wikipedia]

Two.

Autumn colors peaked late this year, reaching well into November in Ann Arbor even past election day. After a nontraditional election season the people spoke and the transition of power is following its honorable historical precedents. What this will mean in terms of health care remains to be seen. The ACA will be problematic to unravel and, with it or without it, deployment of fair and excellent health care, the mission of academic medical centers, and the stability of the health care industry are at risk regardless of whatever party dominates the day. Healthcare has been a hard nut to crack in America and a viable menu of choices for its deployment remains elusive.

The University of Michigan urology microcosm, however, seems reasonably in balance. Last month we completed residency application interviews for more than 60 prospective trainees. The four to match here will begin their 5 years of residency in July of 2017 and graduate in 2022. [Above Medical School foliage. Below view from Bank of Ann Arbor headquarters]

Last month was also notable for its super supermoon (below). The moon’s orbit came so close to the earth that it was larger and brighter than any time since January 26, 1948. Having missed it back then, I took the picture below on November 12. To a lesser degree supermoons occur every 14 months when a full moon occurs at its perigee (closest encounter). More periodically the moon’s oval orbit elongates to create the super supermoon effect.

Michigan Football’s last home game was an exciting victory over Indiana, bringing the first seasonal snowstorm in the fourth quarter when we also saw snow angels on the field during time outs.

[Above: first quarter. Below: fourth quarter from Sincock suite]

The season ended a week later with an unprecedented double overtime loss in Columbus.

Three.

We shouldn’t leave 2016 without mentioning once again, Jheronimus van Aken, the Flemish painter known as Hieronymus Bosch who died 500 years ago. His Garden of Earthly Delights, a triptych in The Prado, depicts strangely imagined hedonistic days of mankind between the Garden of Eden on the viewer’s left and the Last Judgment on the right. Bosch painted the work around 1497, which for historical perspective was five years after Columbus landed on a Bahamian island and claimed the adjacent continent of diverse people, flora, and fauna for the King and Queen of a nation thousands of miles away.

Bosch also painted a strange work called The Wayfarer, mentioned here last month for its stranguria depiction. The world of Hieronymus Bosch around 1500 was probably a pretty grim place, although not devoid of earthly delights, as he imagined in his triptych. A later triptych, The Last Judgement (c. 1527) by another Dutch artist Lucas van Leyden, depicts the actual day of judgment in the middle panel flanked by heaven on the left on hell on the right.

The times of Bosch and van Leyden were framed by fierce religiosity that juxtaposed nations and perpetrated conflicts negating the very values of the religions. Earthly delights, in the minds of those artists and most of their contemporaries, were only a brief interlude before the Heaven and Hell that defined mankind. Native Americans, suffering the European invasion, had no pretension to those ecclesiastical visions of heaven and hell, but rather sought to make the most of their experiential present, albeit with respect to their forefathers and the spirits of their present-day world. It was quite a contrast of civilizations and the Europeans surely brought dimensions of ecclesiastical and actual hell to North America.

Ecclesiastical visions have rightly become personal matters in most of western society. The separation of church and state, as espoused in The Constitution, was a forward step in the self-determination of mankind, although it remains under constant challenge at home and abroad. If The Garden of Earthly Delights is all we can expect in life (before Heaven or Hell) then it should be fair and just, and health care is central to the mix of basic expectations.

Four.

After viewing van Leyden’s triptych at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam early this autumn, while en route to a pediatric urology meeting, I was stopped in my tracks by street musicians playing an enchanting soft tuba staccato note that morphed into the familiar beginning of Vivaldi’s Concerto No. 4, “The Winter.” It hardly felt like winter at the moment, but it was a beautiful interlude. Known as The Red Priest (Il Prete Rosso) Antonio Vivaldi wrote The Four Seasons around 1723 and published it in 1725, coincidentally in Amsterdam. Vivaldi clearly was familiar with the nastiness of freezing rain and treachery of icy paths as seen in the narrative that accompanied his piece (below).

Allegro non molto

To tremble from cold in the icy snow,

In the harsh breath of a horrid wind;

To run, stamping one’s feet every moment,

Our teeth chattering in the extreme cold

Largo

Before the fire to pass peaceful,

Contented days while the rain outside pours down.

Allegro

We tread the icy path slowly and cautiously,

for fear of tripping and falling.

Then turn abruptly, slip, crash on the ground and,

rising, hasten on across the ice lest it cracks up.

We feel the chill north winds course through the home

despite the locked and bolted doors…

this is winter, which nonetheless

brings its own delights.

Winter Solstice will be here soon (December 21) and after that interlude of shortest daylight, each passing day will be a step closer to spring, in spite of “the harsh breath of a horrid wind.”

Five.

Mirror neurons again. Since I read John Berger’s A Fortunate Man last summer, Dr. John Sassall and his deep empathy for his patients in an impoverished English hamlet have haunted me. The lives of those people in the mid 1960s were perhaps not so far removed those Bosch depicted across the North Sea before the Industrial Revolution. While Sassall may seem hypersensitive, he was not so different from the rest of us but for our lesser imaginations. The journalist’s impressions of Sassall’s thoughts are worth repeating.

“Do his patients deserve the lives they lead, or do they deserve better? Are they what they could be or are they suffering continual diminution? Do they ever have the opportunity to develop the potentialities which he has observed in them at certain moments? Are there not some who secretly wish to live in a sense that is impossible given the conditions of their actual lives? And facing this impossibility do they not then secretly wish to die?” [Berger. A Fortunate Man. p. 133]

[Classic photo of Dorothea Lange. Destitute pea pickers in California – mother of 7. 1936. Library of Congress.]

My daughter Emily, a young English professor at Columbia, teaches Aristotle’s three methods of persuasion: ethos, logos, and pathos. Visual art, Dorothea Lange’s photography for example, captures the suffering that troubled Sassall so greatly and should trouble us too. We are insulated from pathos by the professional boundaries of ethos and the logos of our science, metrics, and computers. The grim thoughts of Sassall stretch the role of a physician. Yet, who in society has a greater mandate to defend mankind’s well-being specifically and generally? Clergymen, teachers, and rare politicians share this charge, but day-in and day-out, healthcare providers are most consistently on the front lines with some of the best tools to ameliorate the daily pains and continual diminutions of individuals around us. Urologists and other specialists may claim turf protection, but can’t forget that they are physicians first and foremost. Berger’s last sentence was most likely targeted to the difficult days at end-of-life, the time when the garden of earthly delights has run out – familiar terrain for most urologists.

The toll of pathos was considered by Jennifer Best, from the University of Washington in Seattle in A Piece of My Mind column in JAMA called The Things We Have Lost [JAMA 316:1871, 2016].

“When most people consider the grief endured by physicians in training, they look first to the devastating narratives of patient care – sudden illness, agonizing decline, putrid decay, untimely death, haunting errors, and crushing uncertainty. Even more than a decade from residency, I am pierced by these tragic moments and faces – each still heart-shatteringly vivid.”

Best goes on from this opening statement to suggest not only confronting these griefs in “curricular endeavors” such rounds or narrative sessions with trainees, but also considering personal losses as we play out our roles in what she calls physicianship. Her claim is that when we accept the role of healthcare provider, we step into a new identity and lose some of our freer, ad lib, selves. Growing our sense of empathy, yet maintaining resilience is the challenge. Best rejects counter arguments that her considerations are “first-world problems” or that because “it could be so much worse” we need not be overly concerned with professional fragility. Her column offers a good footnote to A Fortunate Man.

Six.

Department of complaints. We spoke last autumn at some length on medical error and argued that our profession can never be free from it. Error is a fundamental property of life and intrinsic to all its processes. We study error in healthcare to minimize it and fortunately most error is nonlethal, although even when trivial it can hurt. The University of Michigan Health System, like any large scale enterprise, has many processes susceptible to error. With 2 million ambulatory care visits and 50,000 major surgical procedures yearly countless opportunities arise for untoward events ranging from missed blood draws to serious complications in ICUs. Every complaint is a gift, of a sort, providing opportunity for improvements in individual actions, processes, and structures. I recently heard complaints that targeted team leadership factors and the “hotel” functions of hospitalization.

Complaint A. Who is my doctor? Patients generally are thankful about their care from the doctors, nurses, and other members of the team, however fumbled handoffs or inability to identify the responsible member of a healthcare team on any given day are vexing. You can find analogies for this in baseball or air travel industries where the buck stops with the general manager of the team or the pilot. Both endeavors, like health care, require complicated teams, but each fan or traveler can usually identify who is in charge. Health care teams and systems need to make their ladders of responsibility more visible.

Complaint B. Must I share a room? Double room occupancy at UM Main Hospital is a vestige of an older era of health care, but is no longer acceptable for a variety of reasons including privacy, infection control, safety, comfort, and patient satisfaction. Our failure to convert the remaining double rooms over the past 20 years is an embarrassment today and correction is in the works, but it’s nearly a billion-dollar fix including a new patient tower estimated to open in 2021.

Seven.

MACRAnyms. Acronyms abound in most occupations and populate the shop talk that distinguishes workers from the public at large. The big acronym for health care in 2017 is MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. Sponsored by Congressional Representative Michael Burgess (R-TX-26) this act removes the sustainable growth rate methodology for the determination of physician payments and extends aspects of Medicare and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). I can’t pretend to understand this large and complex set of regulations outside of a few salient details, but fortunately we have experts among us at Michigan such as Tim Peterson (below – Medical Director Population Health Office UMMG). Like many well-intended public policies, unintended consequences are inevitable in MACRA, so the better we educate ourselves the more capable we will be to help patients lost in the regulatory shuffle and the greater likelihood we will have to protect the mission and values of healthcare education, clinical delivery, and research.

MACRA attempts to displace the dominant model of physician payment from fee for service (FFS) to payment for value. While it is fashionable to vilify the motivational factors of FFS as a driver of health care expenses (and presumably unnecessary services) there is risk in terms of motivating the restraint of healthcare services. I also recognize a healthcare safety net is direct of a civilized society; universal access to health care is in the national interest. I equally recognize the downside of a system that does not reward work in terms of time and quality.

The intent of MACRA in shifting payment from FFS to payment for quality and value, set by complex government formulas, is an unproven experiment. Market forces should largely determine value and quality, while professional organizations should set basic standards for services. National healthcare cannot be left exclusively to the invisible hand of the market or the heavy hand of government. Healthcare affects everyone, employs one in six people in this country, and is a huge piece of our economy. The present systems of healthcare (there is no single “system”) need huge improvement, but changing it on a massive scale can be dangerously disruptive.

We need various systems of healthcare in simultaneous play, from the private and the public sectors to provide equity, excellence, innovation, and value. The private sector can best supply competition, value, innovation, and stakeholder responsiveness. The public system can best supply the safety net, equity, rules, education, and research. No single system, set of laws, organization, or paradigm can do it alone and we must be suspicious of any grand “answer,” for healthcare is a very hard nut to crack.

Eight.

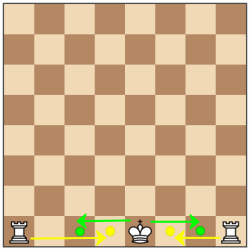

The nutcracker comes to mind at this time of year – not for the compression of urologic structures by the superior mesenteric artery and aorta, but for the ballet based on ETA Hoffmann’s story in 1816, Nutcracker and Mouse King. [Above: Nutcracker collection. Wikimedia Commons] The original story featured a nutcracker whose jaw was broken by an unusually hard nut, triggering political intrigue, revenge, hate, battle, and murder. Alexandre Dumas in 1844 lightened and popularized the story as The Tale of the Nutcracker, that became the basis for Tchaikovsky’s ballet in 1892. It is a rare American community in December where you can’t find an amateur or professional version to attend. You can read a synopsis of the morbid original story in Wikipedia (and perhaps give a modest annual contribution to keep that great public good afloat).

Our own great cardiologist, Kim Eagle, years back as editor of the NEJM section Images in Clinical Medicine, published a classic image of a 52 year-old woman with mild episodic gross hematuria from renal vein compression by the superior mesenteric artery. [Kimura & Araki. NEJM. 335:171, 1996] Improved CT technology offers a better image (below) in a more recent paper from the Mayo Clinic Proceedings. [Kurklinsky & Rooke. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 85:552, 2010]

[Computed tomographic venogram: nutcracker phenomenon.

Distended left renal vein (black arrow) compressed between

aorta and superior mesenteric artery.]

Nine.

Nutcracker politics continue to play out in life and art. The innovative House of Cards on Netflix is a very dark modern political nutcracker story. People need politics, crave leadership, and tolerate a fair amount of nut cracking.

Ideology and celebrity can hijack brains like zombie viruses resulting in political choices and actions that prove contradictory to an individual’s ultimate interests. Politics, a term derived from the Greek “of citizens”, is the process of decision-making and governance of stakeholders. Political systems are frameworks that define acceptable political methods in a given society. Confucius, Plato, Aristotle and countless other thinkers have advanced political thought throughout the history of mankind. Formal politics prescribe public elections, national healthcare policy, and self-government as in our UM Health System. Informal politics are at play in all human activities, real and fictional, even as portrayed in The Nutcracker or House of Cards, where acceptable political methods get conveniently perverted to attain political power.

Politics, whether played fairly or unfairly, are essential to operationalize democracy, which is more of a biologic phenomenon, perhaps akin to quorum sensing, than an ideology or mere political system. This amazing universe of possibilities has arisen from 23 pairs of human chromosomes, their 3 billion base pairs, and 21,000 genes. Civilization is a house of chromosomes.

Ten.

Political parties developed to create candidates for public elections since the days of our first and last politically independent president, George Washington. Our present bivalent political system dates from 1854 when the USA has had two main parties, the then-dominant Democratic Party and an upstart party of anti-slavery activists, modernizers, ex-Whigs, and ex-Free Soldiers. The upstarts coalesced into a Republican Party that held its first official convention in Jackson, Michigan July 6, 1854. Within 4 years Republicans dominated all northern states and in 1860 they won control of both houses and their candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected president. He had a tough presidency and many expected little of him, but Lincoln rose to the occasion of the office and the issues of the day. Two years into his single term, the Union League of Philadelphia was founded. One room (below) features portraits of every Republican president of the United States.

Democratic and Republican parties dominated the American political landscape since Lincoln’s time, while other parties have failed to gain leverage. The Constitution, Green, Libertarian, and other small parties continue to field candidates but attract only small numbers of followers. Candidates for office independent of political party are not uncommon in local elections, but rare in higher office. Washington was the last independent president. Bernie Sanders is the longest serving independent in the history of the US Congress, although he aligns with Democrats. The Socialist Party of America, founded in 1901, never produced much of a winning ticket and dissolved in 1972. The Communist Party USA founded in 1919 was closely tied to the US labor movement, but never gained enough foothold to even have warranted the Red Scares; examples of its failed experiments near to us and in distant nations have dispelled serious interest in modern literate nations.

The 2016 election is over. Democrats will need to reconcile with Republicans and vice versa. The voting closely split the country and each party needs to learn from the other. More importantly both parties need to govern effectively, wisely, cooperatively, and justly. Health care policy is a muddle in the middle of things. Ultimately, though, what really matters above all is financial world-market stability and geopolitical stability. Without these, little else remains, so as with every president – we hope for the best.

[A cautionary slogan for politicians: Glen Arbor Fourth of July Parade, 2012 – Decker’s septic pumping truck with slogan: “another truckload of political promises.”]

Thanks for reading Matula Thoughts this first Friday in December, 2016 – and best holiday wishes.

David A. Bloom

University of Michigan, Department of Urology, Ann Arbor