Matula Thoughts October 3, 2014

Michigan Urology Family

Aspirations, bandwidth, clinical value, & existential epidemics.

3379 words, 12 items.

1.  With the colder and less sunny days of October at hand, it’s refreshing to come back to this aspirational symbol that the Dow Corporation developed to describe what they call “THE HUMAN ELEMENT.” This implies something unique and emergent to our species. Mankind’s days, even on the cold and dark ones, are distinguished by human aspirations that extend beyond the basic drives, common to all life forms, of survival and comfort. Those of us with health care careers are especially compelled by the more complex human drives and aspirations that Adam Smith, Scottish philosopher and pioneer economist, noted in his book The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759: “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.” Then and now, Scotland has been an important intellectual and economic part of the British Empire, although its days within the empire nearly ended just last month.

With the colder and less sunny days of October at hand, it’s refreshing to come back to this aspirational symbol that the Dow Corporation developed to describe what they call “THE HUMAN ELEMENT.” This implies something unique and emergent to our species. Mankind’s days, even on the cold and dark ones, are distinguished by human aspirations that extend beyond the basic drives, common to all life forms, of survival and comfort. Those of us with health care careers are especially compelled by the more complex human drives and aspirations that Adam Smith, Scottish philosopher and pioneer economist, noted in his book The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759: “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.” Then and now, Scotland has been an important intellectual and economic part of the British Empire, although its days within the empire nearly ended just last month.

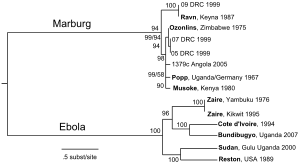

2. Tough days. Days are getting shorter by this point in the year and we find ourselves halfway to that time in the northern hemisphere when human optimism encounters its great celestial challenge from the shortest diurnal stretch of daylight. With the calendar now in its final quarter we can tally a good measure of notable human accomplishments for 2014, although these are counterbalanced by terrible existential threats for mankind including viral contagions and epidemics of extremist sectarianism. Ebola is likely to be a game-changer for civilization and the terrorism perpetrated by fanatic groups is no less horrific, although with less capacity to become global in a matter of days. Curiously both of these threats are infectious diseases – one due to a virus and the other an infectious disease of human thought. The responses of the civilized modern world to these contagions will set the stage for 2015 and thereafter. We have dealt with game-changing infectious diseases before and can overcome these new ones as well, but not without much pain and tragedy. A TED talk by the astronomer Martin Rees filmed in March 2014 touches on human existential concerns and well worth 7 minutes of your time, leaving you with both anxiety for our ultimate fate and optimism for the potential bright side of the human element [Rees. Can we prevent the end of the world? TEDGlobal 2014].

[Ebola cycle, family of viruses & the actual virus – from CDC]

3. Data & information. The positive side of the 2014 ledger to date must include the Second Dow Health Services Research Symposium we held in mid-September. The meeting focused on big data and its implications for health services research. While information may be sensory, narrative, or numeric, it is the numeric information that we call “data.” Big data is the current phrase for data sets too large and complex to manage with simple calculators, tools or traditional data processing applications. Detail about our symposium is beyond the scope of today’s message, so write me if you want a CD of the proceedings. I will come back in future months to the concepts of information and data, but let me cherry-pick a few highlights of the meeting at this time. Stewart Wang presented the amazing morphomics model he built out of big data to manage patients with major traumatic injuries. He also challenged analysts to consider “what is not there” in the data – for example the critical social element behind any information. Jason Owen-Smith explained the importance of social networks to physicians and health care. John Ayanian discussed big data in health care reform. Charles Friedman talked about “learning health systems” and analyzed the Panama Canal as a complex project requiring many forms of data integration including that of social factors, political forces, and infectious diseases. He highlighted Dr. William Gorgas, the chief sanitation officer on the canal project, as the hero of the infectious disease mitigation necessary for success. Craig Sincock, CEO of Avfuel Corporation here in Ann Arbor, showed that a passionate human element is necessary to translate data and ideas into excellent execution of any job, or in the larger success of any business or organization. He explained how context counts; no one can know everything and a team with a diverse crowd of talents on board is able to solve problems far better than a team consisting only of a single set of skills and world-views. Caprice Greenberg spoke about models of learning and new concepts of experiential “student-driven” learning for surgeons to make personal progress on the “asymptotic curve of mastery” (Daniel Pink’s metaphor). While we are focused intensely on data, and big data is a current favorite bit of jargon on the center stage, it is only its interpretation and utility to the human element that gives it meaning and makes it matter. As Craig Sincock told us, and as his company Avfuel proves, it takes enthusiasm and passion to parlay data into meaningful and great results. The symposium was superb, so feel free to take me up on the offer of a CD.

4. Pictures from a symposium.

[My view of the information to wisdom highway]

[David Miller addressing our second HSR symposium]

[From the back of the room]

[Dave Miller, Stewart Wang, John Gore, Khurshid Ghani]

[Craig Sincock, CEO of Avfuel, explaining how passion creates great performance from data]

[John Ayanian and John Hollingsworth in the Big House after Craig’s talk]

5. Bandwidth. A geek might say that soon we will exhaust the calendar bandwidth of 2014. Actually, you and I use that term equally comfortably as it has moved from the world of techno-speak to the vernacular of nearly everyone. Such is the mutability of language, bandwidth now fills an essential niche in modern life. That linguistic space was previously but inadequately filled by terms such as attention or time. We often heard statements like: “You didn’t pay attention to me” or “I don’t have time for this.” These phrases carry the intended message, but wrongly imply a social shortfall of personal needs – the attention that I need or the time that I have. We have come to discover, learning through the technology that we invented, that the real problem is physical limitation – the width of our band – namely the limited capacity of our 8-pound cerebral neuronal network to manage the ambient information.

[Claude Shannon’s diagram of a general communications system c. 1949]

6. Attention pollution. Our brains have been hardwired over hundreds of thousands of years to contend with strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities in changing environments. The parameters of change, however, were finite – limited mainly to feast or famine, cold or heat, predators or parasites, rain or drought, hurricaines or earthquakes, occasional eclipses, and rare meteor impacts. People interacted in finite ways and within finite social units. Complex civilization and modern technology now offer nearly infinite possibilities of change, including interactions with thousands of unwanted friends and linked-in pals. The information available to mankind today, evidenced by the Shannon number (see Matula Thoughts May 3, 2013 on Claude Shannon at matulathoughts.org) and Wikipedia, defines comprehension. Our wireless brains, like our home wireless networks, are limited by the physical constraints of our individual bandwidths. This is especially problematic for modern health care workers, particularly in academic medical centers with triple missions. The doctor-patient relationship has grown unbelievably more complex as the essential transactions of health care, including its educational, discovery, regulatory, and financial facets, now occupy most bandwidth of patients and providers. Personal bandwidth in clinical medicine is terribly crowded and we need to strip out the nonsense that detracts from the essential transactions of patient care. Attention pollution has become a quality and safety concern. Alarms from public address systems, bedside monitors, pagers, smart phones, fire alarm testing, and beepers distract from consistent thought and focus. Federally mandated electronic record systems have further diverted attention from the patient to the keyboard and created avatars of patients made from cut and pasted scripts, dot phrases, and drop down menus that are phony models for actual authentic patients.

[again let me show this picture from Elizabeth Toll: The cost of technology. JAMA 307: 2947, 2012. © TG Murphy]

7.  Big healthcare. We work in a complex and large environment that is short of physical bandwidth and attention bandwidth relative to the essential transactions of healthcare. Last month for the first time in history, our Emergency Department was so overwhelmed on one day that the clinical departments were asked to divert their emergencies to other hospitals. On many other days, it is a standing condition that our ICUs, operating rooms, and hospital beds are fully loaded such that transfers cannot be accepted or routine OR cases have to be deferred. On top of our facility overload we have to factor in the overload of individual bandwidth of health care providers by electronic medical record perversions, regulatory constraints, and all that noise around us. A new normal condition of professional attention deficit disorder is at hand. I was recently asked to bring two renal failure patients from other healthcare organizations into our system at Michigan. One pediatric patient was from another country while the other was a local pre-transplant patient, the wife of a local business owner, and already a patient at a competing system of ours. I think I struck out on the first patient, trying with a number of calls and conversations to hand it off to others to make the connection and get it organized. Regarding the second patient, however, a single call to a colleague did the trick and brought her to UM where she now is in place waiting for next steps in her care.

Big healthcare. We work in a complex and large environment that is short of physical bandwidth and attention bandwidth relative to the essential transactions of healthcare. Last month for the first time in history, our Emergency Department was so overwhelmed on one day that the clinical departments were asked to divert their emergencies to other hospitals. On many other days, it is a standing condition that our ICUs, operating rooms, and hospital beds are fully loaded such that transfers cannot be accepted or routine OR cases have to be deferred. On top of our facility overload we have to factor in the overload of individual bandwidth of health care providers by electronic medical record perversions, regulatory constraints, and all that noise around us. A new normal condition of professional attention deficit disorder is at hand. I was recently asked to bring two renal failure patients from other healthcare organizations into our system at Michigan. One pediatric patient was from another country while the other was a local pre-transplant patient, the wife of a local business owner, and already a patient at a competing system of ours. I think I struck out on the first patient, trying with a number of calls and conversations to hand it off to others to make the connection and get it organized. Regarding the second patient, however, a single call to a colleague did the trick and brought her to UM where she now is in place waiting for next steps in her care.

In de-briefing the family, I rediscovered a few useful facts. Fact number one: most colleagues and services lines here at Michigan are reliable and even though not “hungry for new patients” they are hungry to help. Yes, our facilities and manpower are sadly insufficient for our daily clinical needs. More patients want clinic visits and more of them need operative procedures than our capacity easily allows. Faculty, at considerable personal cost, mitigate this mismatch every day. Too often it takes heroic deeds to solve trivial problems. This mismatch has existed for well over a decade, but it keeps getting worse. Why the mismatch exists is not a complex question. Our organizational structure and leadership(myself included) have not been able to match institutional capacity to accommodate daily clinical needs and seasonal variation.

8. Time. Fact number two: time is important to patients. This should hardly be a surprise, time is important to everyone. For someone facing a kidney transplant who wants to come to the UM, an entry appointment in 1-2 weeks is far more acceptable than one in 6 weeks, even if the actual transplant is not imminent. The time to first appointment for a new patient is a surrogate for “concern” or interest of the clinical service and its physicians (and by extension – “concern of the UM”). Fact number three: people appreciate preparation – and some visible evidence of preparation on the part of the clinician is another surrogate for “concern.” The husband of the second patient said they were quite satisfied with the first visit. My colleagues “squeezed” her into their busy schedules and saw her promptly. I asked what the negatives might have been with the visit (there are ALWAYS negatives – but unless we dig for them we may not understand them). Not wanting to seem ungrateful, the husband said that they liked our doctors and had enough confidence to transfer her care here. However, I could tell there were some negatives and asked what we could have done better. He said that one thing that had impressed him and his wife when visiting our competitor was that those physicians had looked at the notes and chart before they walked into the room. I confess that I haven’t always done this – my bandwidth seems to be pretty full even before I squeeze another patient onto my schedule. However, I believe I need to make this adjustment to make a semblance of introductory conversation that indicates familiarity with the issue at hand. Even cursory preparation allows me to walk in the room with necessary materials – for example if a new patient is a child with posterior urethral valves, I can walk in the room and say something like “I see from Dr. Jones’s note that your child has posterior urethral valves – and I have some reading materials on the problem for you. But first tell me from your point of view what’s been going on.” Patients usually hate to be asked: “why are you here?” (It may sound like – “Why are you bothering me?” to them.)

9. Time again. Fact number two again, we can’t overstate this: time is important. The other thing the husband reluctantly told me is that the visit took 7 hours. As a customer-oriented businessman, while very grateful to have been “squeezed in,” he thought 7 hours was “kind of” a lot more time than necessary. We have become prisoners to our systems and facilities and are not good at creating efficiency for ourselves and our patients. This is part of the so-called value proposition. I think we need to find a way to “concierge” our patients through each stage of care. At the UM we have somehow managed, through the design of our workflows and our facilities to squander time for both our patients and our providers. Other competitors, like the Mayo Clinic, long ago figured that the provider is a crucial rate-limiting factor in clinical care. So if you visit Rochester, Minnesota you see systems built and organized to maximize the efficiency of providers and maximize value to patients. Clinical value is largely a matter of time, perception of expertise, and ability to satisfy a patient’s needs. In my opinion patients want three main things: expertise, kindness, and convenience. The business school rhetoric may be that charges and true costs are key features of the value equation, but clinical value must be viewed from the patient’s perspective, which is rooted in time, perceived expertise, and satisfaction of expectations. We must find ways to mitigate these internal stresses and “self-inflicted wounds” in healthcare of our systems and mindsets because the external stresses are likely to increase.

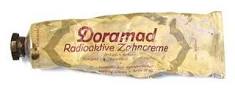

10. Infectious diseases. Among the external stresses we face in health care are the infectious diseases that shape the world. This is nothing new, for they have shaped civilization, individual nations, and even the University of Michigan. Two diseases are of particular interest. The university began its operations in Detroit in 1817, but had to cease operations several times in the 1830s, closing its doors because of raging cholera epidemics in southeast Michigan. This instability set the stage for the relocation of the university to Ann Arbor in 1838. While cholera, a bacterial infection caused by Vibrio cholera, was transferred by ingestion of contaminated water here in Michigan, further to the south on this continent a different contagion, yellow fever, had a another means of spread. This RNA Flavivirus is transferred from person to person by female mosquitoes of the Aedes aegypti species and in severe epidemics yellow fever mortality exceeded 50%. Today, a safe and effective vaccine is available for yellow fever, and mosquito control limits the vector in much of the world. Cholera can be easily eliminated by sanitation and clean water, the very basics of civilization. Nonetheless Vibrio cholera caused the deaths of Peter Tchaikovsky, James Polk, and Carl von Clausewitiz, nearly 10,000 Haitians after the 2010 earthquake, and currently well over 100,000 a year worldwide in a world we have called civilized. Curiously, cholera was unknown in Haiti until aid workers brought in to help after the quake introduced the bacilli via poor sanitation facilities. You can read about it in an article in Science just a few weeks ago: the specific workers were from Nepal where the bacillus is endemic. [Kean. S. As cholera goes so goes Haiti. Science. 345:1266-1268, 2014] As cynics say – no good deed goes unpunished. Cholera remains a huge public health issue in Haiti – in spite of the fact that its prevention is a mere matter of keeping poop from the water and food people ingest. Currently another frightening new threat is in the news – enterovirus D-68. In this day of smart phones and other technological accomplishments of the human element, it makes one wonder why big pharma seems focused on blockbuster life-style drugs with their direct-to consumer advertising instead of looking into the biology, prevention, and treatment of our real existential threats. The same criticism can be leveled at us in universities.

[Cholera & 1919 poster]

[Cholera & 1919 poster]

[Yellow fever virus & vector Aedes aegypti]

[Yellow fever virus & vector Aedes aegypti]

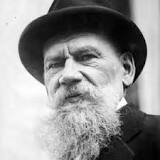

11. This day in history. Every calendar day has its historic overtones, some universally recognized and others obscure, but significant. Back in 1854 in Toulminville (near Mobile), Alabama, William Crawford Gorgas (1854-1920) was born on this particular day. His name is familiar to you as the U.S. Army surgeon of essential importance to the completion of the Panama Canal. Gorgas had parlayed the ideas of Walter Reed (who in his own turn had parlayed the ideas of Cuban physician Carlos Finlay) into eradication of yellow fever and malaria in Havana after the Spanish-American War in 1898. Based on that success he was appointed chief sanitation officer of the Panama Canal construction project in 1904 where he successfully implemented sanitation and mosquito control. He later became president of the American Medical Association (1909-1910) and Surgeon General of the U.S. Army (1914). He died in London on July 3, 1920 shortly after receiving an honorary knighthood from King George V. While the story of Gorgas is of interest, so too is that of the doctor who delivered him as an infant on this day in 1854. [Picture: US Army Center of Military History. The Panama Canal: An Army’s Enterprise. 2009 p. 36. CMH Pub 70-115-1]

12. A curious coincidence. The obstetrician was Josiah Clark Nott, an obscure name today but one I encountered in recent historical studies. Yellow fever was a big problem in South Carolina, Alabama, and Louisiana, where Nott had worked during much of his career. In 1848 he wrote an astonishing paper in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal entitled “Yellow Fever contrasted with Bilious Fever – Reasons for believing it a disease sui generis – Its mode of Propagation – Remote Cause – Probable insect or animalicular origin. etc.” [4:563-601, 1848] This predated the germ theory, Koch’s postulates, Semmelweis’s experiment, Lister’s antisepsis proofs, and the confirmation by Finlay and Reed that yellow fever was transmitted by a particular mosquito species. Ironically, Nott lost 4 of his own children to yellow fever within a single week in 1856 even though he had moved his family out to the country from Mobile hoping to escape an epidemic of Vibrio cholera. Nott’s enduring intellectual history was subsequently framed and marred by his misguided advocacy of polygenesis and white supremacy. Yet Nott’s legacy as a physician, like that of most physicians, is unknowable in terms of the lives he impacted as a caregiver and teacher. The lucky coincidence of Gorgas’s birth as well as the visible remnants of his patient care and teaching evidenced in a few historical documents are all that remains. As with most physicians, however, their impact on the lives of others, perhaps a cardinal motivating factor in their entry into the field of medicine, although incalculable, is a sustaining feature of civilization. We feel this fact most acutely today in the accruing numbers of physicians in West Africa who are succumbing to the effects of the new terrible epidemic that they are trying to mitigate in their patients. Regardless of our individual bandwidths or that of modern society, Ebola and other bad actors are at hand and it will be dealt with – how well we deal with them will be define us. Doctors without Borders and other international volunteers embody the better aspirations of mankind and Adam Smith’s observation that “However selfish soever….” We are hopeful that a few modern-day Gorgas’s or vaccines will turn up to stem the tide of these impeding devastations.

[NBC News DANIEL BEREHULAK / REDUX PICTURE]

Best wishes, and thanks for spending time on “Matula Thoughts.”

David A. Bloom