Matula Thoughts February 6, 2015

Michigan Urology Family

Shapes of content and edges of meaning in winter’s last month.

4020 words

1. The violet, blooming in very cold weather, is a symbol of February and it would be nice to see a few of those flowers in the ground right now. [Image from Wikipedia, public domain, photographer: Shizhao. Taken 2 December 2007 with Nikon D80] The third month of winter is the most orderly of all months – consisting, usually, of four exact seven-day weeks. This February is especially symmetric, a well-shaped rectangular month with exactly 4 perfectly arranged weeks going from Sundays through Saturdays. Geometry like this is mentally pleasing as we like to find or imagine order and symmetry in the world. These aesthetics make the world seem “right” and perhaps help us to find some sense of meaning. February derived from the Latin word februum for purification. In the old Roman lunar calendar the purification ritual Februa was held this time of year at the full moon. From the business perspective, this month is light with only 20 business days, so the onus is on us to make them as productive as possible. In my pediatric urology sphere, this is challenging due to many unexpected cancellations of clinic visits and scheduled operative procedures because of seasonal illnesses in kids. Nonetheless, efficiency – the very essence of the lean process engagement that we are so committed to in the Medical School and Health System – is the best path to a successful future in academic medicine. Consider what 5% improvement in efficiency means to a three billion dollar business. That’s only a matter of 5% less supplies, 5% less time per episode of care (especially when spent on electronic medical record systems), 5% more new patients seen each week, 5% better utilization of facilities, 5% more productivity of health care providers, researchers, and clerical staff. A Five Percent Solution would produce a healthy new normal for our institution in Ann Arbor a year from now. By the way, next year, 2016, will be a leap year with 29 days of February beginning on a Monday.

2. February 6. Two historic February 6 events have overtones today. In 1778 amidst the Revolutionary War the Treaty of Alliance [pictured] and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce were signed in Paris by the United States and France signaling official recognition of America’s new republic. Ben Franklin led the Continental Commissioners and signed both documents. Without France’s contributions at that time, it is unlikely a United States of America would exist today in its present form. In 1820, 86 African American immigrants sponsored by the American Colonization Society (ACS) left New York to start a settlement in present-day Liberia. That story, however, had begun a few years earlier.

Paul Cuffee (1759–1817, illustration from Wikipedia) a successful Quaker ship owner descended from Ashanti and Wampanoag parents, had the idea to settle freed American slaves in Africa and gained support from the British government, free black leaders in the United States, and members of Congress to take American emigrants to the British colony of Sierra Leone. Intending to return with cargo in 1816 he took 38 African Americans to Freetown, Sierra Leone. Later voyages were precluded by his death in 1817, but by reaching a large audience with his pro-colonization arguments and single practical example, Cuffee laid the groundwork for the ACS. During the next three years, the society raised money by selling memberships and pressured Congress and President James Monroe for support. In 1819, the ACS received $100,000 from Congress to purchase freedom for some slaves and to cover the transport costs. On February 6, 1820, the ship Elizabeth, sailed from New York for Liberia with three white ACS agents and 88 African American emigrants. The ACS was unable to get further funds from Congress, but did succeed in appeals to state legislatures. In 1850, Virginia set aside $30,000 annually for five years to aid and support emigration and later the society received additional funds from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Missouri, and Maryland.

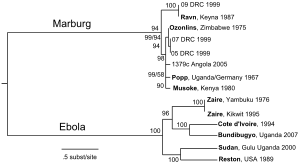

3. Progress. Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, have been prominent in recent headlines with Ebola largely because they lacked the infrastructure to manage their outbreaks. Liberia is a peculiar construct with origins that were both philanthropic and racist. While the so-called racial divides within mankind have been dissolved by science, insofar as skin color is a matter of dermatologic response to climate (see Nina Jablonski’s work in Science 346:934, 2014), overtones of racism continue to mar human progress. This thought begs the question, what is human progress? On one hand we have a.) the progress of science and technology, although some thinkers argue that such progress only hastens the extinction of our species, taking along countless other species as well. On the other hand, there is b.) the humane progress of equality, education, just government, cosmopolitanism, and fair opportunity. The only sane pathway forward is the latter form of progress merged with science, technology, and economies that respect biodiversity and planetary welfare, but how this can be achieved with failed nations, fragile economies, sectarian warfare, ejaculations of terrorism, and lingering racism is our defining question. Progress is a two-edged sword and you can understand the dark side of it in Roland Wright’s provocative and very readable book, A Short History of Progress. The bottom line in my opinion is that the net result of human progress should be to further a decent, self determined life for everyone, and the same for their children on a sustainable planet.

[Ebola map – The Lancet 385:7, 2015]

4. Equality. In an interview towards the end of last year, President Obama said something in his year-end news conference (December 19) that aroused a painful national conversation. In the recent aftermath of the killings of young men by police and point blank assassination of police officers by young men, he commented that in day-to-day interactions America is “less racially divided” than when he took office. This seemed at odds with opinion polls and headline news. We may not feel less divided because issues of racism have been so prominent in the news. Some journalists including Roxane Gay – who reports on race, gender, and identity – agreed with the president noting that these issues are more visible because Americans are being forced to confront a difficult reality, having “been able to look away in the past and we can no longer look away.” [NPR Morning Edition Dec. 31, 2014 interview with David Green] She broadened her comments to include abuses by people in positions of power and a gender rift in which “ … some men feel that women owe them attention, affection, love, sex. And when they are not given what they are owed, there are consequences.” She included examples of allegations related to Elliot Rodger and Bill Crosby. Painful though these discussions may be, in our open society we are able to have these difficult conversations and work through these divides in the hope of creating a better society. This is far from the case in the pseudo state of ISIS and in many places elsewhere in the world. The world is cosmopolitan with 7 billion of us, with no type or group having any more inalienable rights than another. All modern nations should be fair, just, and provide infrastructure for basic human needs and safety, otherwise a claim to nationhood doesn’t pass the muster of reality. Underlying our membership in the human species is the fundamental human moral understanding that everyone deserves a fair shot at a decent self-determined life. This belief requires a commitment to equality, a topic highlighted in Danielle Allen’s work on the Declaration of Independence and her 5 main aspects of equality. These bear repeating: a.) no domination – equality of presence & opportunity; b.) equal access to government and laws; c.) equality in contribution to collective intelligence (everyone’s opinion matters); d.) equality of reciprocity (this one is a key point – the balancing of agency in human relations with the mutual recognition and ability of individuals to recalibrate or redress imbalances in encroachments of freedom); & e.) equality of ownership of public life. Without equality in these 5 forms we have no civilization.

5. Work. Many managers repeat the claim that they want their employees “to work smarter.” This belief carries the conceit that managers, from lofty perches, have access to special insights or technologies that can reform individual productivity at the cottage industry or assembly line level. But really, what worker doesn’t want to work better or more productively, unless circumstances (managers, particularly) provoke a nihilist attitude? An enduring 5% solution is more likely to come from worker-based “smarter work” than a top-down manager-based fiat. It is ironic that throughout all the claims to “working smarter” in healthcare, the talk is related to efficiency and not being better physicians in the senses of diagnostic acumen, clinical skills, communications, kindness, safety, and outcomes. The real magic of our time is found not in the inspiration of a CEO de jour, but rather in the workplace (gemba), where workers using their own expertise of their work and product can unleash their creativity to make things better. This is the idea of lean process engineering, something our organization has focused on sharply. The most salient recent success at the University of Michigan Health System has been the Faculty Group Practice (FGP). This came about when the Hospital in 2007 transferred about 90 Ambulatory Care Units (ACUs) to a regentally-sanctioned clinical faculty group with operational and some fiscal authority. Currently we have about 145 ACUs that are largely managed by the people working within them. We are now transitioning the FGP to a larger organization with greater involvement of clinicians in the strategy, capital decisions, and operational management of the aggregate clinical work of the University of Michigan. The new group will be called the University of Michigan Medical Group (UMMG) – maybe not the catchiest of all names, but it says what it is; the UM Medical Group. New bylaws are being drawn up for this group to define roles and responsibilities that will allow rational and integrated management of our complex health system for the benefit of patients, learners, and knowledge. This is long overdue. Our clinical faculty individually have been swimming upstream trying to provide optimal care for patients, teach the next generation of health care practitioners, and expand the conceptual basis of medicine. The timing for this change is good, with our respected interim EVPMA and alumnus Mike Johns turning over the position to Marschall Runge on March 1. As I write these thoughts I see a new book has just come out by Steven Brill, who authored the Time Magazine single issue called “A Bitter Pill” two years ago. We discussed that work on these pages back then and I’ll come back soon with observations on the book, where he details both the state of American health care and the Affordable Care Act that is changing it.

6. Philanthropy. Pope Francis, perhaps the most philanthropic of leaders on the current world stage, recently spoke of the pathology of power, as we mentioned here last month. He understands better than most of us not only our obligations to others in need, but also how power diminishes empathy. His extraordinary Christmas message to the cardinals and bishops of the Roman Curia, applies perfectly to any large organization whether a department, a business, a university, or a nation. Francis warned against endemic “spiritual diseases of bureaucracy” including the pathology of power, the temptation of narcissism, cowardly gossip, and the building of personal empires. Certainly the Vatican got it right in the mysterious process of leadership succession with him, but this got me thinking why we, as a species, are so inconsistent in this important matter of selecting our next generation of leaders. If Winston Churchill and Mahatma Ghandi were “right” choices as leaders (although they hardly admired each other) Adolph Hitler and Pol Pot were not. Hitler and Pot hijacked their nations and led them into war, genocide, and countless other crimes against humanity. How can a single leader control millions of people, especially if that leader serves interests counter to most of those people? The best defense against this Achilles’ heel of our species seems to be free speech, shared belief in equitable human rights (cosmopolitanism), and representative government. If crimes against humanity are the dark side of human nature, good deeds for humanity are the bright side – and this is the nature of philanthropy. The human species is a wonderfully diverse lot and it is by means of the very diversity, in the Darwinian sense, that the best hope for the future lies. This is the essence of cosmopolitanism. The great beliefs of the Reformation and Enlightenment have led to the work in progress of representative government as you see in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, France, Germany and many other nations. One perplexing irony is within these free nations, extremist views of barbaric individuals are allowed free range. These views can act like mental viruses in susceptible individuals who then translate extremist sectarian or political thought into uncivilized, undemocratic, un-cosmopolitan, and villainous action. Powerful thoughts can diminish empathy regarding alternate ideas and the power of a weapon magnifies the disease.

7. Meaning. Our brains are hardwired to relate to some types of information better than others. Information whether sensory, narrative, or numeric allows us to resolve uncertainty and understand the world. Spatial information and stories, for example, are more meaningful to most people than numeric or abstract information. Spatial information may be sensory – we have proprioceptive skills and we have spatial neurons that mark our place in environments – and spatial information may also be conveyed by analogies, something the human brain does so well. Education, the vanishing species of liberal education most especially, sharpens the critical thinking of individuals, exposes them to a wide range of ideas, and prepares them for life in a cosmopolitan world. Being productive and creative in that world people can meaningfully better that world of today and the world of tomorrow. A colleague and friend here at the University of Michigan, James Boyd White, wrote a book I’ve enjoyed called The Edge of Meaning. The spatial analogy of edge is a brilliant metaphor implying some sort of intellectual border to that space we crave to access, as befits our biologic name, Homo sapiens. [White. The Edge of Meaning. University of Chicago Press, 2001] The Preface begins with this paragraph. “Though we have no very good way of talking about it, one of the deepest needs of human beings – perhaps of all our needs the one that is most distinctly human – is for what we in English call meaning in our experience. It is meaning that we seek to create through our cultures, those complex symbolic and expressive practices ranging from music to politics, football to religion, that occupy us so much of the time; and meaning, perhaps in a somewhat different sense, that each individual seeks as he or she works through the choices and possibilities of existence, trying to make them add up to something whole and coherent.” Powerful thoughts.

8. Content & shapes. In its most basic sense content to a child is stuff in a box. As we grow up we learn that a table of contents is a organized listing of things, most usually in a book. The digital world has broadened our sense of content to include (according to our friend Wikipedia) “information and experiences that provide value for an end-user or audience.” While content is more than noise in the universe, one might argue that some content (experiences and information) might be meaningful to one person, but mere noise to someone else. In some instances what appears to be noise at first, may be perceived as meaningful content after study and analysis. It is increasingly difficult in this age of information, accelerated by the growing world wide web, is to discern content that is meaningful to us individually. This is another level of the signal vs. noise dilemma: some content rises above routine interest or utility in that it provides meaning about our lives with insights into our values, our human nature, and our personal character. We assume such self-reflection is unique to the human condition, or perhaps the “higher ape condition” – who really knows how unique we are? Nevertheless, our brains are fine tuned to search for meaning, as if we need “p-values” for our existence. Another geometric metaphor is found in the title of Ben Shahn’s book, The Shape of Content. Of the varieties of information our brains receive – sensory, narrative, and numeric – the sensory and narrative forms are the one most of us relate to best. Shapes, one might argue, offer a sensory form of information that is both visual and tactile in our imaginations in that you can visually “feel” a circle, triangle, and rectangle. I found Shahn’s old paperback in a funky bookstore in Atlanta. The visual work of the author, a great American artist and illustrator, was familiar to me and my daughter (now an assistant professor of English at Georgia State) but not his written work so I picked up the somewhat battered copy for her. It was curiously priced way beyond its initial cost in 1957. Subsequently I’ve found much cheaper newer editions available though Amazon, but I would never have known of it had I not seen it on the shelf in the eclectic shop. (It will indeed be a minor crime against humanity if the next generation of Homo sapiens has only Amazon for its bookstore.) I have quoted from Shahn before and I keep finding new treasures in his book including this: “Content, I have said, may be anything. Whatever crosses the human mind may be fit content for art – in the right hands. It is out of the variety of experience that we have derived varieties of form; and it is out of the challenge of a great idea that we have gained the great in form – the immense harmonies in music, the meaningful related actions of the drama, a wealth of form and style and shape in painting and poetry.” [Shahn. The Shape of Content. Harvard University Press, 1957. P. 72]

9.  Back to February. While you will find no urological themes in the beautiful shapes and content of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry – its February illumination is well worth a look on these cold days in the northern hemisphere. This work, painted around 1412-1416 for John, Duke of Berry (a Donald Trump of a sort for his day) was a book of hours, a collection of prayers to be said at canonical hours. An illuminated page introduced each month and the February calendar miniature, believed painted by Paul Limbourg, shows a sheep pen, bee hives, and a dovecote next to a small house where three young people and a cat relax in front of a fire. A person on the right seems to be walking to the house while blowing on his or her hands to warm them (you may relate to the frigid scene this winter). In the background a man chops wood while another leads a wood-bearing donkey to a village. Above the painting is an astronomical chart with a solar chariot and signs and degrees of the zodiac. [Illustration from Condé Museum – located inside the Chateau de Chantilly in Chantilly, Oise, 40 km north of Paris] As you look at this quaint genre scene, you may realize that not much has changed in 700 years. People still get on with life, make their livings, seek comfort, enjoy diversion from their work, and look for patterns, harmony, and meaning as reflected in the astronomical chart. Lives come and go, but life musters forward.

Back to February. While you will find no urological themes in the beautiful shapes and content of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry – its February illumination is well worth a look on these cold days in the northern hemisphere. This work, painted around 1412-1416 for John, Duke of Berry (a Donald Trump of a sort for his day) was a book of hours, a collection of prayers to be said at canonical hours. An illuminated page introduced each month and the February calendar miniature, believed painted by Paul Limbourg, shows a sheep pen, bee hives, and a dovecote next to a small house where three young people and a cat relax in front of a fire. A person on the right seems to be walking to the house while blowing on his or her hands to warm them (you may relate to the frigid scene this winter). In the background a man chops wood while another leads a wood-bearing donkey to a village. Above the painting is an astronomical chart with a solar chariot and signs and degrees of the zodiac. [Illustration from Condé Museum – located inside the Chateau de Chantilly in Chantilly, Oise, 40 km north of Paris] As you look at this quaint genre scene, you may realize that not much has changed in 700 years. People still get on with life, make their livings, seek comfort, enjoy diversion from their work, and look for patterns, harmony, and meaning as reflected in the astronomical chart. Lives come and go, but life musters forward.

It is rumored that the first six weeks of each new year comprise the most treacherous span for human mortality, absent the influences of war and natural disaster. I don’t know if this is statistically true, a northern hemisphere phenomenon, or what, but just in the past few weeks 3 dear friends of nearly exactly my age died suddenly and wrenchingly. They each left a lot – great families and friendships to be sure, but more than that. Each had a distinct form of optimism and pluck, perhaps enhanced by previous close encounters of the terminal kind, but probably equally due to their own native kindness and aequanimitas. This last word was a favorite of Sir William Osler who used it to mean imperturbability, although more broadly the term means goodwill, kindness, equanimity, and patience. It is the very essence of humanity and fits so well with Thomas Shumaker, Thomas Adrian Wheat, and Gordon McLorie. Mentioned and shown in order of their loss, each in his own way enriched the content of lives around them, mine included. Humans may be the only species impertinent enough to ask the question what is the meaning of life. Descartes thought it sufficient to understand that “we think, therefore we exist.” James Boyd White suggests that we are capable of going further, to the edge of understanding meaning with the tools of language and imagination. Tom S. (a lawyer and son of one of the founders of pediatric urology), Adrian (Army surgeon and professional grade historian of Confederacy Medicine), and Gordon (fellow pediatric urologist, world traveler, and co-trainee from our UCLA days in the early 1970’s) lived lives of rich meaning. Their families, personal friendships, and professional contributions are certainly exemplary in terms of meaning. Yet beyond that, their aequanimitas, each in its own way, modeled the essence of humanity, how we as individuals stay glued-together enough to muster on constructively to build better tomorrows for our collective children. That process of mustering on with aequanimitas to create a better tomorrow for our descendants is what makes up the meaning and fulfillment of life. These men did it well. All species strive to muster on, but aequanimitas is our human touch.

10. Mission, & essential deliverable (our declaration). How can an organization best carry out its mission and essential deliverables? It helps if the organization’s work is meaningful to society. Even more so, if the work is meaningful to tomorrow’s society, namely that of our children in the broadest sense. If members of an organization are aligned believers in their mission and essential deliverables, the team has a chance at greatness. In doing its work exceptionally, the team can inspire itself, will inspire its learners, and will inspire other teams. Teamwork is the fundamental necessity of civilization and a highly performing team is the most effective and civilized form of organizational function. This brings to mind a sports metaphor and so I return to the 1936 Olympic 8-man rowing crew that is as good an example as you can find. I was on the crew of the rowing team of my small high school in Buffalo New York and we practiced at the West Side Rowing Club, an organization that clearly had seen far better teams performing on the water, so you may be relieved to learn that the sports metaphor is not mine. I can only imagine what we looked like to seasoned observers. So let me return to Dan Brown’s account of the 1936 championship crew from the University of Washington. It’s a compelling and accurate story, mentioned previously in Matula Thoughts, of the formation and performances of a highly effective team, perhaps as fine of an athletic team as has existed. We respond to the beauty of great athleticism and teamwork in all sports, but crew is in its own world, indeed even its name refers to the team and not the actual activity. Unlike baseball, for example, where the team features highly individual performances, yet may execute lovely moments of teamwork, 8-man rowing requires 8 exquisitely coordinated and relentless athletic efforts coordinated minutely and steered by a coxswain making a perfect line through water and space. That teamwork and geometric execution are what we try to emulate with our UM Urology Department, our Medical School, and now with the UM Medical Group.

[University of Washington underdogs, given the least favorable position at top lane, finished ahead of Italy and Germany in foreground]

Best wishes, and thanks for spending time on Matula Thoughts this month.

David A. Bloom

Ann Arbor, Michigan

[Cholera & 1919 poster]

[Cholera & 1919 poster]

[Yellow fever virus & vector Aedes aegypti]

[Yellow fever virus & vector Aedes aegypti]