DAB Matula Thoughts November 6, 2015

Seasons, Movember, Nesbit reunion, the dimensions of academic medicine, politics, feline lives, & other disparate thoughts

3452 words

[Self portrait with dog. Nov 8, 2013]

1. Shadows are longer in November, days are colder, and it gets dark noticeably sooner as 2015 winds down. Autumn foliage, so spectacular this season, is detaching from the trees and recycling on the ground. Most of us are getting ready to hunker down and bundle up for the business of winter ahead as we begin to contemplate 2016. We meter out our lives in seasons and cycles, so with November we enter a sort of fin de l’année, playing off on the French term for the end of a century. Fin de siècle most notably applies to the end of the 19th century, an era around the 1880s and 1890s that was only well understood decades later when historical perspective could account for its significance. The photo below shows Michigan medical students and the hospital in 1880 on a cloudy late autumn day much like today. Their big news would have been the election of James Garfield as president.

[UM Bentley Library. Med students in front of hospital c. 1880]

This was the UM Medical School’s 31st season. The 1880 class, recently graduated, was already practicing medicine throughout the state and beyond. The medical school curriculum had transitioned from a 2-year set of lectures to a 3 and then 4-year program of graduated instruction with laboratory and patient care experience. Today when you walk from our “new” main hospital (it was new in 1986) to the Cancer Center you will pass the class of 1880 picture showing 60 students including 24 women, by my count. Only 4 of the men have moustaches or beards that became so fashionable a decade later (when you continue to view the pictures) and will be more common this month in November due to the world-wide Movember Movement.

A decade later in the 19th century fin de siècle on a similar autumn day these Ann Arbor newsboys are getting ready to hawk the morning papers. That year was midway between presidential elections of Grover Cleveland (first term) and Benjamin Harrison. Newsboys are gone, their jobs made obsolete by technology and nowadays people get their news via NPR, television, or smartphones. Urologists, however, have had Darwinian persistence in the human workforce and technology has actually expanded their reach and role.

[AA newsboys 1890. I can’t give credit to the photographer who obtained this image without a lot more investigation, but after 135 years I figure this must be “fair use.”]

The medical school and hospital have changed much since then and now in our 167th season the signature educational product of our academic medical center has expanded from medical students alone to include residents and PhDs who collectively outnumber the students two to one. Our mission of education, clinical care, and health care discovery remains unchanged since that fin de siècle, but to fit that mission to today’s world we are re-organizing our medical school and hospital under the single aegis of an Executive President for Medical Affairs and Dean, Marschall Runge. The success of this structural change in terms of the optimization of our mission will depend upon three major variables: the operational details currently under construction, the people selected to execute those details, and the productivity (clinical, educational, and scholarly) of our health care enterprise as a whole.

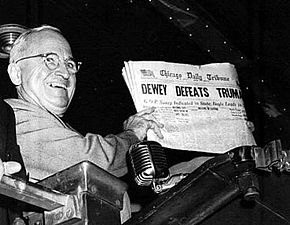

Political rhetoric continues to heat up this month even though major voting is a year away. The U.S. elections are held on the Tuesday after the first Monday of November and the president is elected in even-numbered years at 4-year intervals, so November 8, 2016 will be a big decision point. The contest today looks stranger than ever with providential outsiders competing against highly seasoned and lightly seasoned professional politicians. The consequences of our elections will roll out to residency training programs, medical record systems, and payment methodologies of the not-so-distant future. More importantly, the consequences will be reflected in geopolitical stability and the international economy.

2. The initial urology experiences for most medical students come during third year rotations and fourth year electives when students take clerkships or subinternships at their home schools and visit other places that attract them. At Michigan we had over 350 actual applications for our 4 residency positions. The applicants are clearly the best of the best, although excellent medical school performance and test scores do not automatically equate to great residents, teammates, superb urologists, and Nesbit alumni. It is our job to transform our selected applicants through 5-6 years of residency and subsequent fellowships into extraordinary urologists, educators, and innovators.

The personal statements of our candidates are articulate, show amazing personal accomplishments, and often reflect on the attractions of urology, especially the ability to fix distinct problems with technical wizardry. Yet, I worry how this generation will do with the distractions of the mounting numbers of comorbidities of patients that complicate their “urology issues.” Will urologic detachment blind our next generation of urologists to the inevitable co-morbidities of their patients? Conversely, will patient comorbidities distract young physicians from urologic-decision making or immobilize them to necessary action? How do we teach our successors to understand and even seek out comorbidities so as to attend to their solutions whilst doing the “urology”? Will the growing administrative burdens, including the mandates of the electronic record and duty hour restrictions, further exacerbate their detachment?

As I was reading transcripts, writing letters of recommendation, and thinking about this new season of applicants, I began to reconsider the characteristics we expect of ourselves as people, physicians, urologists, and educators. Seven key attributes seem to apply equally to residents as well as our best selves. To my list of the seven essential attributes for an excellent urology resident I added a bibliography:

A. Kindness. (P. Ferrucci: The Power of Kindness)

B. Authenticity. You are whom you seem to be. (HG Frankfurt. Two books: On Truth, On Bullshit)

C. Cosmopolitanism (KA Appiah: Cosmopolitanism)

D. Curiosity (EO Wilson: Consilience)

E. Literacy. (S Fish: How to write a sentence)

F. Teamwork & leadership. (DJ Brown: The Boys in the Boat)

My little list may or may not prove useful for a “book club.” Although we don’t have time for this in the 80-hour weeks “allowed” for resident education, perhaps our best trainees will pursue this list or one like it, surreptitiously off the grid, for “extra credit.”

3. Nesbit meeting background. Reed Miller Nesbit was the first official head of urology at Michigan. His teacher, Hugh Cabot, had arrived here in late 1919 to lead the Surgery Department and in short order also became medical school dean. Cabot, a genitourinary surgeon of international stature at this time, was such a catch for the university that the regents gave him the president’s house to live in until he got settled. Nesbit and Charles Huggins were Michigan’s first 2 urology trainees, and Cabot seemed to have trained them well. Cabot’s innovative ideas and outspoken nature offended many and he was fired by the regents in 1930.

Nesbit was then named official head of urology within the Surgery Department and he soon became a pivotal figure in American surgery. Huggins focused on prostate cancer research, developed his career largely at the University of Chicago, and earned a Nobel Prize in 1966. Our Nesbit Society was created in 1972. Faculty, UM urology trainees and UMMS students who got their urology start here, but trained elsewhere, are members of the Nesbit Society.

Residency training is an intense period of work, study, and friendships that reverberate for a lifetime. It is a fact lost on lay people and many in the academe that residency training is the career-defining stage of medical education and the signature product of an academic medical center. It is where the professional knowledge base, values, and skills of the next generation of physicians are forged. Whereas UM has close to 700 medical students and 200 Ph.D.s in health sciences at any time, we have 1200 residents and fellows. [Picture above – day one of Nesbit Meeting 2015 in Sheldon Auditorium; below – day two at North Campus Research Complex]

Nesbit 2015. Our Nesbit academic Thursday & Friday were among the best continuing medical education events I’ve experienced and far too much went on to be summarized here. Attendance topped 100 including Tom Koyanagi from Japan, Dave Bomalaski from Alaska, and Jens Sønksen from Copenhagen, along with many other Nesbit alums and MUSIC colleagues from around Michigan. Faculty, resident, and fellows gave superb presentations. Appropos of November, Daniela Wittmann’s talk included details of the worldwide and Ann Arbor impact of the Movember Movement, including significant scientific funding and collaborations for us in AA. Since 2003, Daniela noted, 5 million Movember participants worldwide have raised over $650 million for men’s health, targeted heavily to prostate cancer. Jerry Andriole, our visiting professor from Washington University in St. Louis, gave superb talks on prostate cancer and PSA.

Greg Harden, our featured speaker, was extraordinary. [Above from left: Gary Faerber, Mike Kozminski, Dave Burks, Greg Harden, DAB] Long-time psychologist to our Athletic Department Greg spoke about need to fine-tune our personal “critical self-assessments” and extended the idea of fitness holistically to the three domains of physical, mental, and spiritual fitness – noting the factor of recovery time: the better fit we are, the quicker our recovery from exercise or exhaustion. During the business meeting Gary Faerber, Associate Chair for Education, announced plans for a new resident’s room. While the hospital is footing the half million dollar overall cost, Gary believed that the dinky regulation lockers and minimal amenities should be upgraded so he announced a campaign for Nesbit alums to fund lockers or computer workstations, etc. Many stepped up to the challenge and Jens Sønksen (picture below; Nesbit 1996 and close colleague of Dana Ohl) put us over the top with an amazing gift.

Julian Wan will be turning over the Nesbit presidency to Mike Kozminski next May at our Nesbit AUA Reception and John Wei will become Secretary-Treasurer. In the Big House Michigan led Michigan State until only the final few seconds when a terrible anti-climactic error cost us the game. No doubt the football team will be doing a thorough post-mortem analysis of that game to look for missed opportunities and analyze mistakes. Just like the rest of the university, the Athletic Department is ultimately an educational unit.

[Opening of UM vs. MSU game 2015. Lloyd Carr is honored]

4. We too analyze our mistakes and untoward events. The Morbidity and Mortality Conference is a key ritual of academic medicine. Once a month we have a 7 AM Grand Rounds-type meeting where our residents stand up and present serious complications and deaths that occurred in our urology department. Faculty and residents discuss what might have been done differently and what factors contributed to each complication or death. Lay readers should not be surprised – every week deaths are likely to occur in UM hospitals at large and among our outpatient population; several million people a year pass through the doors of our health system, tens of thousands of operative procedures occur, and hundreds of thousands of people with serious illnesses are hospitalized. Our daily work is serious, not just the actual care of patients, but also the education of our successors with the expectation that they will be better tomorrow than we are today in this serious business of healthcare. Just as important as patient care and physician education, no less essential is the need to expand the knowledge base of urologic health and disease, in addition to improving therapies and delivery systems. These are the three dimensions of academic medicine. As specialists we hone in with great intensity on the urology issues presented to us, but must also probe efficiently for the context of the urology problem – the comorbidities of health and life.

5. The lives of patients are far more complex than the urologic problems that bring them to our clinics. With specialization comes our conceit of detachment. Living in an era of specialty knowledge and skills, we specialists concentrate on our specific fields and as urologists these are urologic matters. It is easiest to do this in isolation from all the other stuff around a patient’s life, but of course we also need to listen to them and recognize, for example, such things as sadness about recent loss of a parent, delaying traffic jams on the way to appointments, awful parking situations, or perhaps unusual heartburn experienced after a rushed breakfast to get to the appointment on time. These issues are not necessarily irrelevant to, for example, the small renal mass that brings a patient in to see us, although we still need to focus on that immediate issue – and the clock is running while other patients are checking in and you may shortly be called to the OR. On the other side of the coin we have all referred patients with unexplained problems to other services only to be told dismissively by a colleague: “it is not cardiac” or “it is not GI” or “it is not surgical.” We get exasperated when other doctors fail to “consider the whole patient.”

6. Few urological problems, few medical problems of any sort, are isolated conditions. Everyone has lives and comorbidities that complicate the medical conditions under inspection in our clinic. These may be dire social situations, family matters, or other specific medical comorbidities. A recent Perspective in The Lancet by Todd Meyers of the Department of Anthropology at Wayne State University offers a compelling view of this additional dimension of our health care paradigm.

“Comorbidity is a clinical and conceptual problem. It is simultaneously a problem of how to describe multiple morbidities – clinically or epidemiologically – and a problem of how individuals themselves conceptualise and wrestle with their polypathia … Through the play of disorder and circumstance (and presentation and expectation), to treat is to capture, to arrest symptoms in a particular moment, but rarely is there enough time or resource to discover where these symptoms fit within the complex lattice that makes up the individual experience of comorbidity.” [Permission of Todd Meyers. The art of medicine. How is comorbidity lived? T. Meyers. The Lancet. 386:1128-1129, 2015]

You and I will never find the perfect balance between truly understanding a patient in terms of comorbidities of life and body and the immediacy of the person’s urologic condition. The art, however, is in our effort to try as we practice medicine patiently, one patient at a time.

7. Comorbidity, as a term and idea, is attributed to internist and epidemiologist Alvan Feinstein who spent his career at Yale School of Medicine. His reputation has been challenged due to some statements during a period of his career when he minimized the negative effects of smoking, even though he had been sponsored by the industry. [Feinstein, Alvan R. (1970). “The pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic disease”. Journal of Chronic Diseases 23 (7): 455–68] It is easy to pile on indignantly to this criticism now, in 2015, but the overwhelming evidence today of the destructive effects of tobacco smoke was not so apparent back then. Later in his career, particularly as editor of the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, he became more critical of tobacco. Smoking looked cool in the mid-nineteenth century, and the makers of cigarettes naturally tweaked the composition of their product to enhance the addictive features. Ironically, smoking has turned out to be a major contributor to today’s medical comorbidities.

Feinstein, born in Philadelphia December 4, 1925, died just about 15 years ago (October 25, 2001). He obtained bachelor’s, master’s, and medical degrees at the University of Chicago, where he probably interacted with former UM trainee Professor Charles Huggins. In spite of that likely intersection, Feinstein chose internal medicine for a career and trained at the Rockefeller Institute, becoming board certified in 1955. [Picture from Yale Bulletin & Calendar Nov. 2, 2001] After a few years at what would later become the NYU Langone Medical he moved to Yale in 1962 and became founding director of its Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program in 1974.

8. November brings Thanksgiving to mind. The Norman Rockwell painting Freedom from Want (discussed on these pages last March) had its debut on March 6, 1943 as a Saturday Evening Post cover. This was number three in his Four Freedoms series of oil paintings inspired by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union Address. Rockwell started this particular painting the previous Thanksgiving in 1942, depicting actual friends and family at the table. We are too comfortable today to feel as viscerally about the four freedoms as Roosevelt, Rockwell, and most Americans did during the darkest days of WWII or as the world’s 60 million refugees must feel today, but we should beware that our comfort rests on only a thin veneer of civilization. As specialists we are also sometimes too comfortable in our professions. We enjoy not only the four freedoms of Roosevelt (freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear), but also freedom to choose one’s work, in our case the specialty of urology. Board certifications and hospital credentialing processes define our scopes of practice, while varying degrees of personal detachment allow us to focus specifically on urologic disorders and their treatment.

9. On this particular day in history two now-obscure events left countless social and physical comorbidities reverberating still today. In 1965 Cuba and the United States agreed to an airlift for Cubans who wanted to come to the United States. When the Cuban revolution began in 1959 the U.S. government initially reacted favorably to it, but after hundreds of executions and Fidel Castro’s embrace of communism relations soured and by 1965 the Communist Party was governing Cuba. Amazingly, Castro is still around, having survived as Cuba’s leader parallel to 11 American presidents for 16 terms of office. By 1971, 250,000 Cubans had made use of this program. Only now, 50 years later, do we find signs of improvement in relations with that nation of 11 million people only 90 miles away from Key West, Florida. A second historic coincidence occurred exactly 40 years ago on the other side of the Atlantic. The Green March was a strategic mass demonstration in November 1975, coordinated by the Moroccan government, to force Spain and General Franco (ailing despite recent recovery from a serious bout of phlebitis) to hand over its colony, the disputed, autonomous Spanish Province of Sahara. Some 350,000 Moroccans advanced several miles into the Spanish Sahara territory, escorted by nearly 20,000 Moroccan troops and met very little initial response from either Spanish forces or the Sahrawi Polisario Front, an independence movement backed by Algeria, Libya, and Cuba which was fortified by Soviet arms. The Spanish Armed Forces were asked to hold their fire so as to avoid bloodshed and they removed mines from some previously armed fields. Nevertheless, the events quickly escalated into a fully waged war between Morocco, Mauritania, and the Polisario, once Spain left the territory. The Western Sahara War, as it came to be known, lasted for 16 years. The color green was incorporated to invoke Islam. A cease-fire agreement reached in 1991 remains monitored by the UN Mission for the referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). What these two events have in common is the disruption of people’s lives when colonialism, regionalism, and independence movements collide and become playing grounds for larger international proxy conflicts. Sound familiar?

10. November refers to the number nine in Latin, a quantity recalling the alleged lives of a cat. Reflecting back over the shoulder of human time, you can’t help but think that our species has been testing the limits of our existence with far more numerous close calls than a cat’s. The Cuban missile crisis was just one close call, among other instabilities around the planet from Africa, to the mid-East, and in far too many other places. The feline proverb dates back at least to Ben Johnson’s play written in 1598, Every Man in his Humor. William Shakespeare performed in that play and then used a similar phrase a year later in his own play Much Ado About Nothing: “What, courage man! What though care killed a cat, thou hast mettle enough in thee to kill care.” The actual intent of the word care, was worry or sorrow, but somehow over the intervening centuries curiosity became the perpetrator of the cat’s demise. Possibly the belief in 9-lives is related to the ability of cats to land on their feet. In fact their spine is more flexible than that of humans; while like most mammals cats have 7 cervical vertebrae, they have 13 thoracic, 7 lumbar, and 3 sacral vertebrae. We humans have 3-5 caudal vertebrae fused into an internal coccyx, but cats have a variable number of caudal vertebrae in their tail.

[English tabby cat. 1890. Popular Science Monthly Vol. 37]

It is also curious, if we may re-employ the term without penalty, that while cats may have 9 lives and often have amazing moustaches (that remind us of Movember throughout the year), dogs unequivocally remain mankind’s best friends.

|

Thanks for considering our Matula Thoughts once again. Best wishes for Movember, 2015. David A. Bloom |