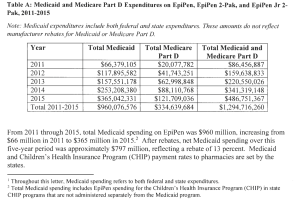

DAB What’s New Nov 3, 2017

3742 words

One.

The matula, an historic symbol of the medical arts and title of this electronic periodical, was the transparent beaker used to examine urine in the pre-scientific days of health care, as people sought explanations for and expectations from their illnesses. Fear and uncertainty exacerbate human illnesses and our earliest prehistoric ancestors found comfort from their fellows in clans and caves to care for and sometimes heal them. The matula is a useful metaphor for the acts of looking, listening, and examining evidence to discover what really matters in clinical situations.

In ancient days what really mattered to people with illness or injury were the issues of treatment and prognosis: what can be done to help, what comes next, will I live, or will I die? The specific matter of diagnosis was most likely subsumed by the idea of what caused the problem. Gods, fates, cosmic forces, evil-doers, bad luck, or obvious injury were likely culprits before germ theory, organ-based dysfunctions, or other explanations based on a verifiable conceptual basis of health and illness. A sense of prognosis, however, was of practical value.

Uroscopists inspected urine for color, consistency, clarity, sediments, smell, and sometimes taste of urine, to find clues for treatment and prognosis. This was not illogical. Pink urine from infection or trauma might be followed by recovery. Gross blood and particulate sediments would suggest recurrent bladder stones. Scanty concentrated urine from dehydration might signal severe gastroenteritis and a grim prognosis. Uroscopy grew into a complex pseudoscience with fanciful claims of prognostic significance based on intricate characteristics of urine samples. Newer tools, such as the stethoscope and microscope superseded matulas and the future will bring better tools.

Thoughts about the future occasionally slide into dystopian visions and invite the question: what really matters to each of us? Putting aside occupational questions of healthcare professionals (making a diagnosis, ascertaining a treatment), political ideology (conservative or liberal, R or D, libertarian or socialist), or pragmatic issues (where do I live, what car do I drive, what’s for lunch?), we each have our own beliefs, although ultimately most people share similar fundamental desires for safety, comfort, and peace of mind. Family and friends matter.

We cherish personal liberty, physically and intellectually. Beauty, curiosity, and clarity matter. Social matters are important to most people; kindness, truth, integrity, respect, belonging, and sustainability are essential in a civilized world. The last item may seem a bit out of place, but as we sustain health, welfare, independence, and safety, for ourselves, our families, our communities, and our descendants, by simple logic we need to sustain our environment.

Two.

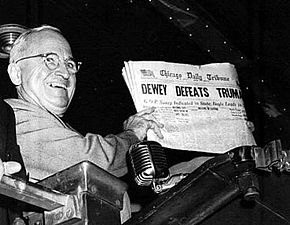

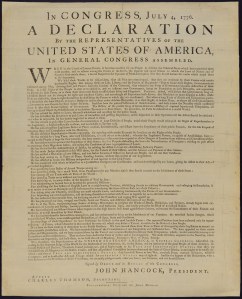

With Michigan’s gorgeous autumn colors fading in the rear-view mirror, November’s matula brings Thanksgiving into sight and notably the iconic holiday images of Norman Rockwell. His Four Freedoms paintings, based on Franklin Roosevelt’s State of the Union Address in 1941, illustrated the freedoms that FDR thought mattered greatly: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. These freedoms extended the sense of the liberty entrenched in the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, – that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, …”

Roosevelt’s four freedoms are more specific than the liberty mentioned in The Declaration at the dawn of the Revolutionary War, although political liberty was not far from Roosevelt’s mind when he gave the speech 11 months before the U.S. entry into World War II. The speech also slyly broke with America’s non-interventionism, by advocating support for our allies already in armed conflict. The words of Roosevelt and paintings of Rockwell mattered greatly to Americans in the 1940’s and they seem to matter now in this new century. Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in 1943 and were used in war bond posters and postage stamps.

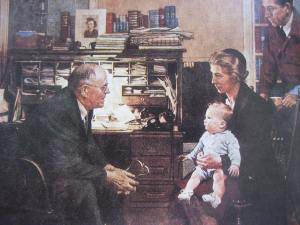

Rockwell also painted enduring images of healthcare professionals, some modelled on his neighbor Dr. Donald E. Campbell. After this topic was discussed in previous pages of WN/MT (March 4 & May 6, 2016) the doctor’s great granddaughter, Moira Dwyer, kindly sent us information and photographs that the family kept. Dr. Campbell, born in 1906, graduated in 1939 from Middlesex Medical School and practiced in Stockbridge, Massachusetts providing nearly the full spectrum of medical care to his community. He retired at 83 and died in 2001 at 95. Like the English physician, John Sassall, detailed in John Berger’s book, A Fortunate Man, Campbell was an indelible part of his community, providing far more than clinical services for patients by going beyond the specificity of medical conditions of his patients to understand their co-morbidities, inner needs, and social constraints. [Matula Thoughts Oct, Nov, Dec. 2016 & Feb. 2017]

As a footnote to Dr. Campbell, Middlesex College of Medicine and Surgery was founded in 1914 in East Cambridge, Massachusetts and was affiliated with a hospital of the same name. The campus moved to Waltham in 1928 and by 1937, it also included schools of liberal arts, pharmacy, podiatry, and veterinary medicine in addition to its school of medicine. Accreditation by the AMA became problematic, ostensibly due to issues of funding, faculty, and facilities although many claimed the merit-based admission policy and unusually diverse student body of Middlesex grated on the far more homogeneous American medical establishment at mid-20th century. Medical schools then maintained ethnic and religious admission quotas and Middlesex was an unabashed outlier with its diverse student body. In 1946, the Middlesex trustees transferred the charter and campus, with the hope that the medical and veterinary schools would be continued, to a foundation that created Brandeis University two years later. Middlesex Medical School did not survive the transition to the new university.

Three.

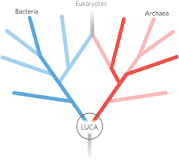

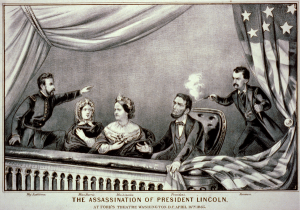

It is a profound community asset to have a Campbell or Sassall and it is impossible to fully measure their impact as a citizen, leader, mentor, and role model. These essential anchors of society bring not just their professional skills, but also their values, leadership, and expectation of fairness to a community. They look out for the common man and particularly for the most vulnerable members of the community. It is no coincidence that a universal ploy of anarchists, revolutionaries, and authoritarian pretenders as seen widely across the planet, is assassination of these “honest brokers.” The moral example and leadership of doctors such as Campbell and Sassall is our ultimate expectation for the medical professionals we teach. These mentors and role models act as epigenetic factors for the larger “superorganism” of humanity. They are operational factors between human genetics and civilization.

Education and training of physicians changed since 1939 when Campbell graduated medical school. The 4-year curriculum deepened with the growing scientific basis of biology and disease while graduate medical education (GME) also expanded with enlarging technology and new specialties of health care. The period of residency practice and study is now the career-defining facet of a doctor’s learning. Nearly 80 years since Dr. Campbell’s graduation, medical students enter fields of GME in as many as 150 areas of focused medical practice with learning experiences that may exceed twice the years the trainees spent in medical school.

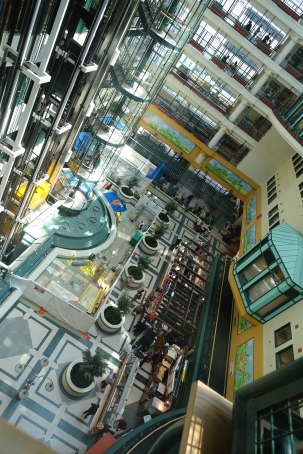

Healthcare education differs from that of lawyers, engineers, and most other career paths. Physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and dentists require an immediate educational context of patient-care. The University of Michigan recognized this fact in 1869 when it converted a faculty house into a hospital, thereby becoming the first university to own and operate a medical center. We recognized this anew when we began to create a wider health care network, in the past few years, capable of supporting our large educational mission, now educating 900 MDs and health care PhDs, 1100 residents and fellows in medicine, as well as dentists, nurses, and pharmacists. One could easily argue that universities should offer a wider coherent educational milieu. A grander educational vision to include all parts of the health care workforce (physician assistants, surgical scrub technicians, medical assistants, etc.) would have a great effect on state economy and on our workforce pipeline. It could be done with robust partnerships not only with the UM Flint and Dearborn campuses, but also with our adjacent and regional community colleges.

Four.

In its more rudimentary days, the UM academic health center was distinguished by its implementation of fulltime clinical faculty, terminology indicating that physicians who practiced or taught exclusively within a teaching hospital had a fulltime salary independent of their patient care revenue at that site. In the early days of UMMS this model attracted national luminaries such as Charles de Nancrede in 1889 and Hugh Cabot in 1920. de Nancrede was an attending surgeon and clinical lecturer at Jefferson Medical College, among other Philadelphia medical institutions, and was a major name in American surgery as a clinician, teacher, and pioneer in antiseptic and aseptic technique. At Michigan he presided over the construction of the new West Hospital in 1892, established a world-class surgery department where he practiced exclusively, and wrote an influential textbook of surgery. [World J. Surg. 22:1175, 1998.] Cabot was an even more stellar addition, coming from Boston as an internationally known urologist, where he had become disillusioned by the monetary nature of medical practice.

The world of healthcare practice, education, and investigation is different in the 21st century. The few academic medical centers that will survive well in the future will be those with the best and brightest geographic fulltime faculty, the majority of whom will be busy clinicians. Their milieu may well depend upon robust clinical productivity that brings the most challenging clinical problems to them and their facilities, but this will also require a very substantial volume of more routine clinical work as the context for education of all learner groups and clinical trials, in addition to inspiring basic science investigation. This clinical milieu will require a robust array of endowed professorships to give faculty a modest disconnect from clinical practice to allow teaching and academic work.

Five.

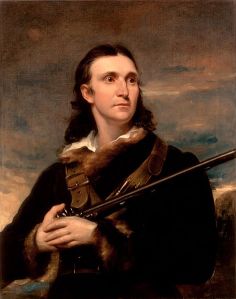

Fellow professionals. Modern specialty-based health care has shifted emphasis from individual all-knowing utility-player doctors like Campbell and Sassall to large teams that deliver their parts of today’s healthcare. The knowledge base, growing list of specialties, and technology of medicine today is so great that the centrality of a single physician is a model that no longer works well for health care delivery. Furthermore, linguistic confusion arises as other terms are awkwardly deployed to indicate all healthcare providers (not just physicians) more inclusively. This matter became acute as we have been creating bylaws for our new University of Michigan Medical Group (UMMG). A good nomenclature solution arose from Gerald Hickson, a Vanderbilt pediatrician (above), speaking to the UMMG this summer about programs that build professionalism and create a culture of safety. His phrase, fellow professionals, nicely includes MDs, DOs, nurses, PAs, physical therapists, podiatrists, occupational therapists, optometrists, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical assistants, etc. [Hickson et al. A complementary approach. Acad. Med. 82:1040, 2007]

Six.

Medical professionals are under stress today from many sources, but the idea of a career in medicine still drives some of the best and brightest young people into our work, as judged by the medical school and urology residency applicants we see each year. I’ve just read applications, personal statements, and letters of recommendations from nearly 70 candidates for our 4 positions to start next July, and again I am blown away by the breadth and depth of these fourth-year medical students who will, all too soon, become our successors as urologists. They will have to resist the pressures to commoditize, corporatize, and industrialize their work as the 21st century rolls along. The electronic record is one of the pressures. A paper in Health Affairs last April surveyed primary care physicians and found they spent 3.17 hours on computers (desktop medicine) for every 3.08 hours spent with patients. [Tai-Seale et al. Electronic health record logs. Health Affairs. 36:655, 2017.]

It is impossible to predict the world that will envelop our successors. The conceptual basis they will learn and the skills they acquire are merely momentary assets. Ideas and techniques will change as long as human progress continues. The values, mores, social skills, curiosity, imagination, and ultimate kindness of our successors will be the principle assets to distinguish their careers, their effects on their communities, and their value to society in general. The influence of their ambient role models is as important as the book-learning and clinical skills imparted in graduate medical education. The epigenetic nature of values, mores, social skills, and role models show us, our colleagues, and our successors how and when to deploy the vast stores of information and skills we have accumulated. Just as importantly, some among them will be inspired to discover new knowledge and develop new skills.

Seven.

With Thanksgiving coming up, I’m appreciative for precarious and relative world peace, food security, respite from climactic disasters, and the happy, healthy, lives we may have. [Above: Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth, 1914, Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts.] The great minds who have made this world so interesting are another blessing, people who looked at the world with clarity to make observations or find patterns that escaped everyone else at their moments.

The name, Conrad H. Waddington, probably doesn’t spring to mind, but is worth consideration. Born on a tea estate in Kerala, India, around this time of year in 1905 this British developmental biologist introduced the concept and word epigenetics. At age four he was sent off to England to live with family members while the parents remained at work in India for the next 23 years. In England, a local druggist and distant relation, Dr. Doeg, took the boy under his wing and inspired his interest in sciences. At Cambridge, “Wad” took a Natural Sciences Trips (a flexible curriculum across sciences) and earned a First in geology in 1926. With a scholarship he studied moral philosophy and metaphysics at university, assumed a lectureship in zoology, and became a Fellow of Christ’s College until 1942. During WWII he was involved in operational research for the Royal Air Force, and in 1947 became Professor of Animal Genetics at the University of Edinburgh where he worked for the rest of his life except for one year at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. Waddington’s landmark paper in 1942 begins with four lovely sentences.

“Of all the branches of biology it is genetics, the science of heredity, which has been most successful in finding a way of analyzing an animal into representative units so that its nature can be indicated by a formula, as we represent a chemical compound by its appropriate symbols. Genetics has been able to do this because it studies animals in their simplest form, namely as fertilized eggs, in which all the complexity of the fully developed animal is implicit but not yet present. But knowledge about the nature of the fertilized egg is not derived directly from an examination of eggs; it is deduced from a consideration of the numbers and kinds of adults into which they develop. Thus genetics has to observe the phenotypes, the adult characteristics of animals, in order to reach conclusions about the genotypes, the hereditary constitutions which are its basic subject-matter.” [Waddington. Endeavor. 1: 18-21, 1942]

Later on the first page he suggests the term epigenetics to encompass the “whole process of developmental processes” that carries genotypes into phenotypes. The influence of Dr. Doeg, whom Waddington called Grandpa, was no doubt significant. The specifics of Dr. Doeg eluded me as I read about Waddington. Too bad, because it would have been illuminating to understand the nature of the fruitful mentorship that shaped Waddington’s curiosity, lucidity, communicative skills, and sociability that left him a context to discover what he did.

Eight.

Black Bart, legendary stagecoach robber, committed his last robbery on this date in 1883. He specialized in Wells Fargo robbery, and it’s a bit ironic that the bank’s more recent history indicates it has internalized that larcenous bent to its own customers. Black Bart was actually Charles Earl Boles, variously known as Charley Bolton, a gentleman bandit in Northern California and Oregon. Born in Norfolk, England, he and his brothers joined the California Gold Rush in 1849. The brothers died and by 1854 Charles was married and living in Decatur, Illinois with a wife and four children. After serving in the Civil War he returned to California and gold prospecting in 1867, leaving his family behind. In 1871 Bolton wrote his wife and described an unpleasant encounter of some sort with Wells Fargo & Company agents and vowed revenge. He fulfilled the vow, adopting the name Black Bart, and robbed at least 28 coaches in California and Oregon, although never fired a weapon or harmed anybody. The last known robbery was in Calaveras County, between Copperopolis and Milton, when he was wounded in the hand while escaping. Detectives found personal items at the scene and through laundry marks traced a handkerchief to a San Francisco laundry on Bush Street. They quickly located Boles, living in nearby boarding house, and convicted him of the November 3 robbery.

Black Bart served four years at San Quentin and after release he was constantly shadowed by Wells Fargo detectives. In a letter to his wife he said he was tired of the attention, and disappeared after being last seen near Visalia on February 28, 1888. A distinctive feature of Black Bart was that he was consistently a gentleman, always polite and never using profanity. It might be said that he was a rare and exemplary professional in his business, living according to his values. His sense of mission will never be exactly known to us today, but Black Bart was somehow compelled to right some perceived wrong and, like most of us, he needed an income so Wells Fargo was a fitting opportunity.

Even in his risky occupation Black Bart remained kind and harmless, other than theft from a corporate entity of questionable kindness itself, it turns out. If he could act kindly in spite of living on the edge as he did, health care professionals such as us might consider him as a role model, although somewhat of a peculiar one. Somewhere along the line he must have had the parenting, mentorship, or experience that built his character of kindness, larcenous though it might have been. [Above book cover. Black Bart: Boulevardier Bandit. George Hoeper. Word Dancer Press, 1995]

Nine.

Jack Lapides. As we unearth stories of Michigan Urology, colorful anecdotes come to light and many involve Jack Lapides. The personal story of a patient who underwent a life-changing Lapides vesicostomy was told on these pages in July and that gentleman was ultimately laid to rest in a ceremony at Arlington in August. Another story from a former medical student was that of Jack teaching the students the art of cystoscopy when he would ask the students to peer over his shoulder and look through the scope to describe what they saw.

It is said that Lapides sometimes mischievously disconnected the light source cord as someone leaned in to look and occasionally an uncertain student provided a fanciful description of the dark or black field. This may have been one origin of his Black Jack moniker, although just as likely it might have been related to the fear he struck among rookies in his expectation for high standards and excellence. Dr. Lapides’s conferences were legendary. He was exacting and tough, requiring that all presentations be stripped of jargon and abbreviations. The IVP, for example, was intravenous pyelogram. Conferences today are more causal. The tradition of teaching conferences persists, but on a larger canvas since Lapides’s days with 4-5 faculty, our scale having increased by a factor of 10. Just below is Thursday morning Grand Rounds. Further below is the Friday AM Mott imaging conference that follows a formal review of operations scheduled the following week. In both instances we have outgrown our rooms.

Yet another Lapides anecdote turned up last week when I was at the American College of Surgeons (ACS) meeting and spent an evening with Lou and Ginger Argenta (below: with Tony Atala of Wake Forest, in San Diego October, 2017).

Lou had been our plastic surgery head in my early years at Michigan and innovated, with Michael Morykwas at Wake Forest, the Vacuum-Assisted Closure (VAC) device, a paradigm-changing system to manage burns and wounds. For this he won the Jacobson Innovation Award from the ACS in 2016. Lou recalled how Jack Lapides, in his retirement years, took up welding and small engine repair, learning and teaching them at Washtenaw Community College. Jack kindly performed a welding repair on the broken bicycle of young Joey Argenta, and the work held up for years of further bicycle abuse.

Lapides stories will undoubtedly continue to emerge. The man and his work had a long reach.

Ten.

What really matters to us, to our patients, to our colleagues, to our community, and our 7 billion global brethren is a deep question usually lost in the daily hustle of life. Most people have roughly similar ideas about what matters, although each has a particular take on things. Donald Campbell, Charles de Nancrede, Charley Bolton, Jack Lapides, Dr. Doeg, CW Waddington, FDR, and Rockwell had their particular world views that shaped their legacies. All, no doubt, shared many of the things that mattered to them, although each likely ordered and interpreted those characteristics idiosyncratically, perhaps Black Bart most peculiarly.

It is no accident that the four essential freedoms that Roosevelt identified have a strong basis in health care. Freedom from want is most obviously tied into food security, but it could just as easily be interpreted as freedom from needs that rationally include shelter and health care. Freedom from fear was illustrated by Rockwell as a fear of illness, but safety and personal security could just as easily have been the visual that Rockwell used. Liberty in the political sense is not so far from liberty in its mobility sense. An authoritarian regime may enforce curfews or travel restrictions, just as health conditions restrict people from being out and about to participate fully in society. If governments are to promote life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, the four freedoms are essential.

Human values and role models are the factors that translate human beings into the superorganism of human civilization. Those factors can go the way of apoptosis or can epigenetically build a prosperous, just, beautiful, robust, and sustainable version of itself for the next generation.

[Autumn foliage, my neighborhood 2017]

David A. Bloom

University of Michigan, Department of Urology, Ann Arbor